Professional-Quality Translation at Light Speed: Why Voice Recognition May Well be the Most Disruptive Translation Technology You’ve Never Heard of.

I’m sort of amazed translators working into English today still type out their translations on keyboards. Hunched over for endless hours at a time, day after day, banging away on an electronic version of a 19th century invention – a barely improved technology from Gutenberg’s movable type of the 15th century – all the while straining their fingers, eyes, wrists, back and weary souls.

It’s slow. It’s tedious. It’s exhausting.

It’s also why translator productivity keeps banging its head up against that relentlessly stubborn 2,000 – 3,000 words-per-day concrete ceiling.

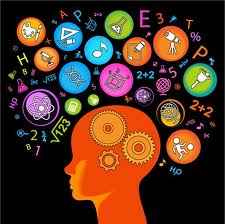

It’s about time to ask ourselves this: Why are we translators in the 21st century caught in a typing trap? Human speech is five to seven times faster; cognitive processing about ten to fifteen times faster. Our translating brains actually work closer to these speeds – something any simultaneous interpreter can tell you – not at the interminable slog rate imposed by the need to pound out individual letters one by one on a keyboard.

Voice-recognition: It almost seems like magic

Modern voice-recognition technology in English, on the other hand, has finally matured in speed and accuracy to the point where you can’t even talk faster than the computer can process your voice and turn it into text on the page. Believe me, I’ve tried. On several occasions recently I’ve attempted, just for fun, to outrun my English voice-recognition software (Dragon Naturally Speaking Professional Edition 11.5) by reading as fast as humanly possible from a finished text. I can’t do it. The computer always keeps up with me.

It’s blisteringly fast, it’s always available, it never gets tired, it’s scarily accurate and the translation quality is professional human quality.

OK, that last part is me. But still.

Voice recognition today enables professional-quality translation at light speed.

A Professional Translator’s Dream

Voice recognition is a professional translator’s dream. The translator simply “speaks” the translation out loud into a headset microphone and lets the computer handle transcription, control and navigation. So the translator is essentially recording a sight translation. Here are some of the many advantages of voice recognition in translation:

• Improved translation quality and stylistic voice. You can radically improve your ability to “stay in the moment” with the text in the conceptual cognitive process without any kind of physical distraction. Vocalizing the translation for me consistently improves the stylistic quality of the target English text because it adds my ear as an additional aural filter. Speaking the translation out loud also blocks source-language interference and inelegant constructions in my mind.

• You are freed from the time lag imposed by the keyboard. Even though I’m a reasonably accomplished touch typist (70 – 90 wpm) the physical act of typing and jumping back and forth with my eyes from source document to target computer screen – or even within text and dialog boxes on screen when using TM tools – has always been very costly to my thought process.

• You are no longer slave to the plodding, strenuous and unnecessary strains of typing. By that I mean not just fatigue and potential injury to fingers, wrists, neck and back in the long run, but the cost of physical exertion and posture distortion – and sitting for hours – every single work day. By contrast the only equipment I use in dictation is a very thin, lightweight digital headset that I sometimes forget I even have on.

• Voice recognition allows you to automate every interaction you have with your computer and still work with TM tools. So you can still use all the tricks and shortcuts and macros and TM tools you use now, and you can also edit and revise text, but now you just say them out loud instead of type them and the computer executes them for you automatically.

• You can make a lot more money. Actually that’s a bit of an understatement. An accomplished dictating translator working in a very familiar field can produce 1,500 – 3,000 words per hour. Yes, you read that correctly. Per hour. It’s a draft translation (to be sure) and you will still need to revise it (always). But by using dictation you can increase your output – and your income – by around fourfold. This is one of the very many reasons that dictating translators very rarely complain about their incomes.

Caveats and Cautions

I’ve long proselytized on the virtues of dictation, dating all the way back to the Cretaceous Period of the 1980s when I began with an old cassette tape dictation machine and two full-time technical typists.

The first day I began dictating translations in the 1980s I almost couldn’t believe how much easier it was. I finished an 8-hour job in about an hour and a half and I just sat there, sort of stunned. I wasn’t quite sure what to do with the rest of my day.

In the late 1990s when I was running workshops and training seminars at ATA conferences, translators coined the term “Hendzel Unit” as a kind of shorthand to refer to my 10,000-word-per day production level by dictation in scientific and technical translation. So I’ve been at this for a long time.

It turned out that this approach came with some caveats, though.

• High-output dictation only works in fields and language pairs you know exceedingly well. I could dictate science and technology in a flash, but I’d worked hard to develop the subject-area expertise and translation skills in those areas. When I expanded into legal and financial translations later in the 1990s, for example, I was dismayed to find that I simply couldn’t dictate those texts. It took nearly five years before I had the subject expertise and familiarity to do it with ease.

Since dictation is a way to connect your mind to the page faster, your mind and voice need to be faster than your typing fingers are. If your mind does not work quickly enough in a given language direction or subject area, there will be no real benefit.

• You may need a bit of interpreter DNA nested into your genetic code to verbalize translations. Humans process spoken language and written language through different cognitive processes – even different pathways in the brain – so those areas need to be able to talk to one another. But most dictating translators I know are not working interpreters, so perhaps only a bit of that DNA is all that’s required.

• Professional-quality voice-recognition software must be available in your target language. This is a major stumbling block for some translators, as are the limits on the ability of English-language software to recognize certain forms of accented English. You can still hire typists to transcribe your dictation, but voice-recognition by definition is dependent on the availability of suitable software.

• Dictated translations are still drafts that require revision and editing. As you develop and refine your dictation skills you will reduce the volume of editing required, but it’s important to recognize that dictation is never a substitute for text revision and polishing.

• Higher-end computer hardware is required. Voice recognition software runs best on very fast processors with as much RAM as you can get – 16 GB is a great start – with a solid-state hard drive (ssd) ideal. This hardware configuration has only recently become reasonably affordable, but do expect to pay a bit more for hardware than is required for other applications.

The poor stepchild of translation technologies

Voice recognition has remained in the shadows as a translation technology principally because there’s nobody out there – beside the individual translators – who reap the enormous financial benefits from its use. In other words, there’s no immediate or ongoing financial benefit to anybody else along the translation food chain other than the translator.

By that I mean that in the TM and MT technology market, unfortunately, it seems that there’s always some non-translator with a hand in your pocket trying to sell you a platform or a tool or a technology where some of the ultimate cost benefit goes to your customer and not you. Not so with dictation.

Turn the per-word market to your advantage

Your mileage, as they say, may vary. But dictation is worth considering, especially when discussions of translator income seem unnecessarily focused on per-word or per-hour rates instead of on total output and productivity, especially in the case of dictation, where the productivity improvement remains 100% in the translator’s pocket.

So if the market insists that you be paid by the word, take advantage of that. Leverage technology and your own skills to deliver, on a regular basis, a dramatically larger volume of high-quality words.

Your bank account – and your weary fingers – will thank you for it.