Confirmation Bias: Why Collaboration is the Path to Translators’ Best Work

A great pitfall in scientific research – and in everyday life – is the very human penchant to see what we want to see rather what is actually there. In psychology and cognitive science, this tendency to filter reality to bolster our own views, theories or explanations is called confirmation bias. It’s deadly in scientific research because it drives well-meaning and quite dedicated researchers to interpret evidence in a way that’s unwittingly partial to existing beliefs or theories, which skews results, blocks valid conclusions and often points in the wrong direction.

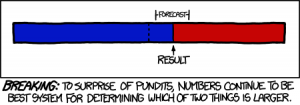

Confirmation bias also explains why we think our political views, for example, are self-evident to all rational people, and why those holding opposing views must be mistaken. In the extreme, political punditry in the U.S. owes its entire existence to confirmation bias. People seek out news, entertainment and commentary that support their particular viewpoint. It’s one reason why people on the losing side of the recent U.S. presidential election were so (genuinely) shocked by the outcome.

Frequency illusion

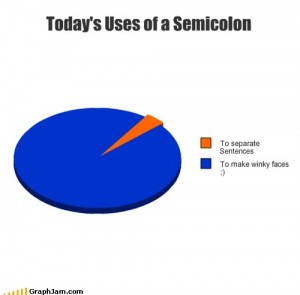

Then there is the frequency illusion in confirmation bias. Translators are very familiar with this phenomenon. It occurs when we first learn a new word or concept and then suddenly start seeing that word or concept in use everywhere (this also happens with popular songs, movie titles and obscure celebrity names, among other things). It’s not that any of these are more common, it’s just our reality-perception filters have changed. Where we once subtly ignored what we didn’t recognize, we now promote them in our mental RAM to stand out in stark contrast.

Experts are the worst

What’s even more troubling is that confirmation bias seems to get much worse with increasing level of expertise. The more prominent and confident the physician or attorney or plumber or cattle wrangler, the more persistent is their tendency to favor their existing beliefs over alternative explanations or new evidence or even paradigm changes. This goes a long way toward explaining Einstein’s absolute refusal to accept the quantum world in his lifetime, despite the saintly patience of Niels Bohr in attempting to persuade him.

Natural selection

Confirmation bias is a deep-wired and persistent behavioral response in humans that was selected for in a hostile world where there were profound survival advantages to making quick decisions based on familiarity (“familiar = safe”) at low biological cost.

It turns out that our minds are not wired to seek “truth,” or even objective accuracy.

Confirmation bias is an intrinsic, built-in feature of human thought and the only way out in science is through careful experimental design, rigorous statistical analysis and skilled peer review – peers outside your own bias bubble.

No rescue from rational thought

The psychologist David Perkins has determined in studies of gifted university students that while IQ was the most powerful indicator of a person’s ability to argue, it turns out that it only predicts that person’s ability to defend positions already held. It was a poor indicator of the ability to argue either side from facts. The emotional overruled the rational. Perkins found that “people invest their IQ in buttressing their own case rather than in exploring the entire issue more fully and evenhandedly.”

Research on confirmation bias conducted by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber, French cognitive scientists, validate this. They found that our evolutionary intrinsic biases and errors in reasoning destroyed any notion of objectivity in rational thought. “Skilled arguers are not after the truth, but after arguments supporting their views.”

Translation is largely intuitive, not rational

My point in beating up on rationality above was not to trash empirical analysis but to emphasize that there’s a great deal of evidence from psychology and cognitive science that humans are quite often emotional thinkers, not rational ones.

This is even more true of the craft of translation, which is a high-focus process of intense cognitive construction via a blizzard of decision-making. In a typical translation we make thousands of decisions, some visible and rational, but most invisible and highly intuitive.

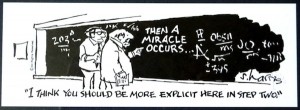

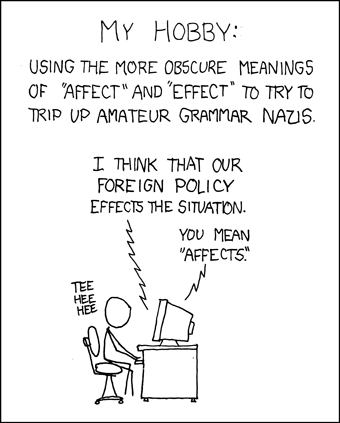

The process is so intuitive that we translators often have a very difficult time explaining to others exactly how we make all these conceptual choices and on what basis. This process has always reminded me of the famous Sidney Harris cartoon on physicists:

Translation as domain-hopping

What we translators do is map our understanding of a reality in one domain over into a completely different domain. Translation at its core goes well beyond manipulation of language symbolics – it’s really domain hopping, much like listening to an aria and then painting a picture to represent your understanding of what you’ve just heard.

So into this stew of deeply intuitive reasoning and rampant confirmation bias we mix the frank reality that most of us work alone. Massive electronic interconnectivity has mitigated this isolation to a significant degree, but that only works when translators seek out assistance from their peers on a regular basis.

This also requires that translators “know what they don’t know,” which is a bit of a logical paradox – if you don’t know something, how could you possibly be aware of not knowing it?

It’s easy to ask a question about a term or phrase or concept you doubt, but what if all those terms you are sure you know are….wrong? Or there’s a better, more concise, and elegant way to say them? How can any of us really improve in any meaningful way without constant, ongoing, direct and honest feedback from our peers?

Self-revision and confirmation bias

It’s also a truism that successful translators are their own worst critics. We revise and self-edit endlessly and can barely release a text from our clutches. If it weren’t for deadlines, we’d never finish a translation job.

What makes this situation a bit dicey is that even the most self-critical among us suffers from confirmation bias. It’s that little itch that we scratch when we find what we think is a perfect solution, only to recognize years later that it was in reality a B- or C+ solution and the A solution never even occurred to us at all.

The late Ben Teague and I used to swap stories on the old FLEFO translators’ forum about how much we deeply hated reading our old translations. This was why. With the benefit of greater experience and enough distance from the text to free us of confirmation bias, the stark reality of our blinding errors would jump right off the page.

Collaboration to the rescue

In group settings it’s far too much to ask of humans with their cognitively biased brains and deep self-image investment to be completely fair-minded, objective, straightforward and honest about their own translations when their reputation and self-interest are on the line. It’s too daunting for us to even see objectivity hiding in the weeds.

Our brains are simply not built that way.

The way around this dilemma is to invoke the wisdom of peers in a group setting. We are far more insightful and less burdened by self-image threats when examining the work of others. Key to the success of such efforts is to put everybody’s work up for collective review – this creates the safest environment where there’s a shared investment in a common objective.

This is why collaborative workshops at ATA conferences or Grant Hamilton’s recent “Translate in the Townships” event or hands-on regional workshops can feel both invigorating and refreshing. Wisdom becomes an emergent property, an entelechy, of the social group.

These same dynamics can be achieved through virtual collaboration, a practice I fear is in decline in today’s translation industry. At the top end of the translation market, though, collaboration is very nearly enshrined as a guiding principle of best practices.

And there is a very good reason for this. It works.