Translators as Language Police: A Linguist Explains Why Some Translators’ Persistent and Puzzling Grammar Nazism is Spectacularly Bad Linguistics

November 16, 2012

Recently I dated a young woman who spoke the most alluring South-Central Virginian dialect.

In terms of Standard American English, it was a linguistic train-wreck. Double negatives, bizarre compound past tenses, subject/verb fistfights and mellifluous pronunciation found deep in the Shenandoah and exactly nowhere else on Earth.

It just charmed me cross-eyed. She figured this out soon enough, and whenever she didn’t get my attention by texting me, she would call me up and talk to me and I’d melt.

Her dialect, though, was a source of deep shame and embarrassment to her. She was forever being “corrected” by people who were fiercely jealous of her and she knew that when she was in Fairfax, Virginia, she sounded different from other people at her university.

Charmed by Language

Linguists – those trained in the scientific study of language – are never put off by this non-standard usage and interpreters regularly embrace it. Language people are fascinated by distinct dialects, odd grammars and regional peculiarities. Training in linguistics changes your ear for language, and you stop hearing “correct” or “incorrect,” and of course it never even occurs to you to actually correct others’ language usage in everyday life. Who in their right mind would ever do that? No trained linguist ever, ever does this.

No, wait. Some translators do!

There is an unfortunate and persistent undertow of Grammar Nazism among working translators that is puzzling, confounding and deeply troubling.

It’s also catastrophically bad linguistics.

I’ve spent huge swaths of my career in this endless battle to disabuse writers, translators, and other language folk – often young, inexperienced ones struggling to find their way in the world – of the notion that grammar is a Holy Grail that must be protected, like some 18th-century virgin’s honor. This is often the result of unfortunate intellectual violence done to young students by badly trained teachers with some deeply seated conflicts of their own.

Language as Instinct

As Steven Pinker has so eloquently set forth, language is a deeply human instinct. We all weave language like spiders weave webs – instinctively flawlessly, brilliantly. We all do this from a young age, in all languages and cultures, and without formal training of any kind.

Grammar jihads by well-meaning but deeply mistaken armchair pundits – and some translators in our industry – are based on an arbitrary and ever-changing set of rules developed by linguists, grammarians and lexicographers to standardize how we communicate. The crucial idea here is “communicate.” If you understand the meaning of what a speaker or writer intends – irrespective of the grammar – then they have succeeded in communicating.

Life in the Hyper-Educated 21st Century

Unfortunately, language professionals in day-to-day life today often find themselves engaged in an internal cognitive battle against endless years of damage caused by these misguided “purists” telling them that there was one “correct” way of speaking or writing, and everything else was wrong.

What they should have been taught, of course, is that there are “standardized” forms that are generally agreed to based on conventions developed by linguists working in a whole host of disciplines and who are the first to admit infinite distance from infallibility. These standards change and are in dramatic flux constantly, because language itself is a bottom-to-top phenomenon.

In other words, language springs forth spontaneously from the human mind and, by definition, any form of communication between humans that succeeds is language.

Any human effort to codify or standardize language is secondary, of lesser importance, of lower rank.

In fact, the only reason to codify language at all is to homogenize spelling and grammar usage so that the language that the people are already speaking – the real language, the language that has the universal authority – improves mutual intelligibility across geographic distances. That’s all.

The dictionaries, the grammars, the rule-books and everything you’ve ever been taught are forever behind, are of secondary rank, are bringing up the rear, and are simply compiled to try to catch up with the real language.

The real language is whatever language you are already speaking and writing.

Education does not teach us language, so how we speak cannot be attributed to the presence or absence of education (recognizing that formal education is still a powerful status marker in language use, of course, but trilingual truck drivers in Switzerland are but one example of living language having nothing to do with advanced university education).

We communicated by language hundreds of thousands of years before we became literate. Language’s natural form is speech. The written form is an arbitrary abstraction, one we have used to form rules only very, very recently — for most of the populace, only within the last 300 years or so. Before that, humans communicated perfectly successfully through speech without formal education, dictionaries, or people to correct them who were in fact themselves often at variance from the very standards they were trying to enforce.

Tribes and the Psychology of the “Other”

What did exist all along was the ability to differentiate one’s group or tribe from others by use of speech. This is a deliberate, specific, programmed part of human speech generation. We are designed to produce dialects — they are hard-wired into our brains from birth. So prejudice has nothing to do with education — it has everything to do with “the other,” the way “other” tribes or groups speak, and how it is different from the way we speak.

In the context of a tribal environment, we did not like foreign dialects. We didn’t think they were “proper.” We thought it was OK if they spoke a dialect there, but not here. These are all ways of pointing our fingers at another person or group speaking a perfectly acceptable, even beautiful, dialect, but one that sounds funny, or strange or “wrong.”

It only sounds “wrong” because it feels like it’s not “ours.”

This is how racism and other forms of ugliness can grow so quickly from waters this infested with misunderstanding.

The Explosive Blast of Language Evolution

Spoken language, e.g. the “real” language, evolves every single day because of modified usage that is more efficient, or introduces new concepts or allows things to be said in a simpler way. Spoken language evolves much faster than written language.

The written language was codified broadly very, very recently, specifically to allow people with different regional pronunciations to understand each other, e.g. to assure that radically different pronunciations of words did not lead to widespread misunderstandings. It also codified spelling and usage, but recognized, almost worshiped, regional variations.

This happened specifically because literacy became more widespread and there had to be some agreement to link together the variations.

Linguistic Snorting and Foot-Stomping

If a translator insists on complaining at great volume about certain people ignoring or misunderstanding or refusing to follow or otherwise being ignoramuses about the arbitrary grammar rules, then that tells us more about the complainers than it does about their targets.

- Youth and innocence are great drivers of leaps of faith and risk-taking that we can all applaud. But it’s a terrible wager to bet the house on the wrong horse. The obscure rules of language we all learned in a desperate bid to survive grammar school aren’t even valid anymore. If you doubt this, take a look at any “authoritative” English grammar from the 1960s. It will shock you how wrong it has become.

- Perhaps more disconcerting is that none of these were “rules” to begin with, but more like temporary guidelines.

- An embittered focus on grammar over content is the ultimate “can’t see the forest for the trees” problem. As language people, translators should be expected to know the basics of linguistics. Several generations of research in sociolinguistics tell us that the most ardent Language Police practitioners are typically over-reaching socially; they lack self-confidence and assuredness.

- In every language studied, the most vociferous Grammar Nazis are, in socioeconomic terms, the “low-status” speakers.

- Perhaps most troublesome is what lies under the surface. The practice is unfortunately a complete and somewhat tragic capitulation to the tribal prejudices deeply embedded in our linguistic consciousness that I’m sure all well-meaning and educated people – like translators – trust they’ve outgrown.

And yes, I know all about how punctuation changes meaning, how inadvertent errors can derail ideas and how standards serve a greater good. And for broad-dissemination print publication – or even a blog like this one – let’s all agree to observe the standards we’ve all decided to adopt specifically for these media.

But let’s also recognize that grammar rules in the larger world and in every other walk of life are in every important way totally arbitrary. They change constantly and it’s the truly creative writers who push those envelopes and redefine the boundaries. Rap and R&B are among the most beautiful examples of this creative destruction.

Language use is a profoundly personal thing. Value what it tells you about people and how they choose to express themselves. You will learn new things, I promise, and have a lot more fun in the journey.

Interesting… it made me think of my first Russian instructor, who stated her opinion that “there are no bad words” when a fellow student asked her to teach us some Russian swear words. Her point was that these taboo words only have as much power as we choose to give them. I feel the same way about some “substandard” dialects in the United States.

Over dinner one evening at the recent ATA conference, a fellow linguist told several jokes involving characters speaking in a southern accent, all of whom were of low intelligence. I thought it was in poor taste, considering the present company (including myself, a sometimes southerner). But I wonder if I am guilty of this sin in writing – one of my pet peeves as a technical writer is the proper use of spacing between numerical values and units, especially degrees of temperature. Am I a grammar nazi when it comes to scientific and technical writing? I think I am. But when a client hires me to edit or proofread, isn’t that what they’re paying me for?

Hi Amy. Thanks for your response.

When you’re hired to edit or proofread a text written for a professional publication-level target audience, you’re being paid to bring that text into conformity with prevailing publication standards. That’s a very specific application of the written language and I think all reasonable people — and certainly all language professionals — would agree that your devotion to doing a good job in that case is not Grammar Nazism.

And of course these are “standards,” not “right” and “wrong.”

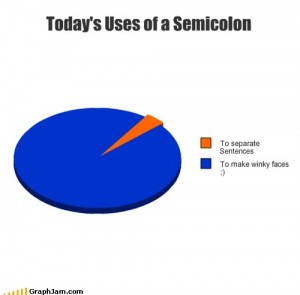

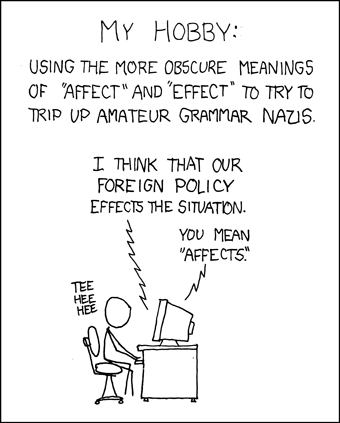

Anyway, a good litmus test for crossing the line into poor behavior is whether the purported error changes meaning or interferes with understanding as well as the context of language use. So, for example, in the cartoon I have in the text above, the difference between “affect” and “effect” has no impact on the meaning of the sentence at all. The urgency to “correct” it is comes not from the desire to connect or understand or further the communication. It derails the communication into a meaningless side discussion where the “corrector” is trying to put down the other person and simultaneously elevate his or her own standing.

And it’s a chat on the Internet. Why in the context of a chat on the Internet would one derail the discussion to score points?

I tried above to emphasize that the real problem comes when translators and other language professionals take the rigor of standards out of the context where they belong (such as your editing of a publication-ready text) and shove them into everyday life where the conventions on language use are dramatically different. The research suggests that there are psychological and social status reasons behind that behavior.

I think non-language people intuitively understand that Grammar Nazism is exceeding poor behavior, which is why the cartoonist “gets” the joke and expertly conveys it.

Thanks again for your comment!

Like you, Kevin, I love listening to variations in people’s speech, whether it’s accent, regionalisms, or the unique markings of an individuals speaker’s idiolect. In my experience, too few translators and too few editors have experience in linguistics.

You highlight a very important point: “correctness” to the detriment of real communication does no one any good. However, I always tell my clients that context is everything. Someone who is hired to do technical writing (like Amy above) should indeed conform to accepted standards for the industry, document type, etc. Copywriters who publish web content destined for thousands of customers would do well to adhere to standard spelling and grammar conventions (unless they’re purposely playing with the language). But “grammar trolls” who pounce on errors in someone’s tweets (as, for example, some followers of John Cusack do http://www.popeater.com/2010/04/29/john-cusack-twitter-trolls/) need to relax. The fastest way to turn someone off is to correct her speech or writing, unless, again, you’ve been hired to do so.

One thing stuck out for me in your post, and that is “in every language studied, the most vociferous Grammar Nazis are, in socioeconomic terms, the ‘low-status’ speakers.” Can you direct me to this source, please? My professional experience says otherwise. But then again, I know a lot of other copyeditors and I used to work as a language tester for the FBI. The overwhelming majority of these people are indeed Grammar Nazis. Interestingly, whenever I would ask them to explain WHY a certain rule must be followed, they could never give me an explanation besides “It’s just wrong.”

Great post. Thanks for publishing.

Thanks, Matthew, for your thoughtful comments.

The pioneering research on low-status speakers predominating in hypercorrection dates back to William Labov’s pioneering research in the 1960s. More recent studies confirming this finding have been published in the last 20 years by Daniel Preston, Nancy Niedzielski and Deborah Cameron.

It’s also amusing that the “violations” of the rules that drive Grammar Nazis insane are far more likely to be adopted in future standards, whose purpose is to standardize actual usage. In other words, the “mistakes,” which of course are just deviations from arbitrary standards, are the most likely to be adopted in future standards.

By the way, have you heard the song “Oxford Comma” by the band Vampire Weekend? You should take a listen, just for fun:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P_i1xk07o4g

Well said, Kevin. Such arrogance needs to be exposed, so it does (as we say in Ireland, but never write lest the wrath of the grammar nazi chaps bear down upon us and on our children’s children for, who knows, maybe

darn, my new iPad thingy sent the comment afore I’d finished it….as I was saying (before I was rudely interrupted, Mr Apple) …for, who knows, maybe 77 generations.

I’m an Irish teacher and we have three major dialects but no spoken standard (though there is a written standard [which, of course, dates back at least 3,000 years….kidding!]).

I enjoy pointing out to my students that the other dialects aren’t different….they’re just wrong. At that point, I invite one of them to come up and extract my tongue which is firmly embedded in my cheek! 🙂

I enjoyed this article. Only yesterday, I was listening to an interview of Noam Chomsky by Lawrence Krauss (https://youtu.be/Ml1G919Bts0). Chomsky makes similar points in this conversation about language.

He, however, says that language happened in human society only about 75,000 years ago, and not hundreds of thousand years ago as you mention, before which we were similar in our communicative ability to other simians and life forms such as bees, which mainly use symbolic language, which is devoid of the ability to think.

According to Chomsky, the primary purpose of language is not communication, but thinking, and the way our thoughts are expressed, either in written words, or in sounds emanating from our mouths, are external to the real purpose of language. Much of our use of language, never gets out of our minds in any form, and is for our own individual use.

The languages we use in translation are a much restricted, stylized, standardised sub set of the vast linguistic edifice that exists in our mind. The styles and standards have to be separately learned, whereas the linguistic ability itself in genetically present in equal measure in every human being.

A very interesting conversation which I recommend every language professional should listen.