Bad Advice for Novice Skydivers: “Learn As You Go.”

December 11, 2013

Why the First, Best Lesson I Learned about Translation Was a Healthy Fear

I was a poor, scrawny white kid with crooked teeth who grew up in the barren hills of central Arizona.

The year before my birth, the Soviets launched Sputnik, shocking the world, and causing a frantic U.S. Congress to allocate funding for fast-track training of the next generation in science and the Russian language. These were dollars that flowed downhill and into the deserts and chaparral country and back woods to us public school kids who played in dirt schoolyards and chased lizards and lived in makeshift trailer parks carved awkwardly into the hills.

Just a few short years later, I found myself working as an intern, holed up in a tiny library with sunshine pouring through ornate windows in the Smithsonian Castle building on the Mall in downtown Washington, D.C. I was hunched over Lenin’s majestic speeches and Trotsky’s galloping histories and Chekhov’s heartbreaking stories all printed on the high-acid paper and stained covers that smelled like pungent sour milk.

A tall man with striking full head of hair stuck his head in the door.

“Kevin, come upstairs with me. We’re having lunch.” He smiled.

I smiled back, but a little flame of terror flickered in my heart. I knew that lunch would be attended by brilliant visiting Soviet scholars who spoke no English, and that new Smithsonian staff had been invited to welcome them.

They spoke no Russian.

The smiling man in the doorway inviting me to join them – James Billington, the renowned Princeton scholar of Russian history, who was later to become the Librarian of Congress – needed me to help him interpret those meetings.

I was 19 years old.

In professional settings where Americans revel in the promise of youth – and I was half the age of every other person in that room – Russians are inherently suspicious and dismissive of it.

I confess that back then I agreed with the Russians. I was desperately counting on my youth to excuse my upcoming performance. I felt in every fiber of my being that I had no right to be in that room.

It turned out that I made it out of those lunches alive, perhaps a bit worse for the wear.

Certainly sweatier.

But looking back, that terror of desperation and self-doubt is a key reason I was later to succeed at professional translation – an activity where I was actually paid for my work.

And yet a bit of that nagging fear has really never left me.

The audacity of translation

Translation is an audacious act.

It requires not only that you know what you know – easy enough, for sure – but it also requires you to know everything the writer knows, too.

And those writers are nuclear physicists, biochemists, patent litigators, financial analysts, neurophysiologists, auditors, mechanical engineers, oil field riggers and a thousand other experts in every field imaginable.

That reality makes fear and doubt your ally in commercial translation. You are, after all, charging real money to convey those complex ideas with authority. In that environment, doubt is useful and essential. It drives you to drill 100 miles deeper into your subject-matter expertise every single year, to seek out feedback and guidance and training, to collaborate and consult with your expert translator colleagues, and to revise and rethink and rewrite, and then to tear it all up and start all over again.

Doubt is what taps you on the shoulder and politely suggests that if you can’t even remember where you left your car keys on Tuesday, what else has unknowingly slipped out of your cognitive grasp?

Even after a lifetime of experience, confidence is just a seduction.

But when you’re just starting out, confidence is deadly.

Seduced by Confidence

Into this mix comes the oft-repeated and puzzling advice that beginning translators can “learn as they go.” “Pick a subject that is ‘not too technical,’ they are told, “and learn on your own.”

This is terrible advice for newbie translators, just like it’s rather catastrophic advice for novice skydivers.

(Skydivers just fall to earth faster.)

Where novice translators get into trouble is that they are seduced by confidence. Without the underlying experience that comes from making and learning from a mountain of mistakes, they conclude that they are in fact excellent translators because they’ve decided – with absolutely no other experienced translators around to review them or correct them or shake them out of their foolish complacency and rampant confirmation bias – that the first rendition of a translation they produce is just perfectly fine.

If you are a translation customer in the commercial market who has seen the results of this philosophy – as I have been for over two decades – this stratospheric overconfidence can be deeply troubling. But I learned a long time ago – the hard way by spending many hundreds of hours re-writing translations produced by some very well-known translators – that translators who had

1) Formal university-level training in their subject-matter areas;

2) Practical training in that discipline; and then

3) Extensive practice and supervision under the keen eye of other working professional translators for, oh, say six additional years correcting all their mistakes before they begin working for clients;

pretty much guaranteed that their product would be unlike all the other translation products out there – and it would show.

And it does show. It shows now.

The worse-kept secret in the translation industry

Translation buyers in the quality sector of the market actually talk about who is good and who is not, and who produces at the top of the field and who does not, as well as why that is so.

It’s almost always the presence or absence of very strong subject-matter expertise and writing skills, but also the benefit of massive collaboration with colleagues.

And the phenomenon is not just restricted to the high-level expert technical fields. I would argue based on my own experience that this overconfidence extends deep into general and non-specialized translation, and infects even the simplest legal contracts or agreements or balance sheets or even personal letters.

Contempt for Clients

What’s even more disconcerting is how the “learn as you go” philosophy is damaging to translation clients. It implicitly treats clients with what borders on outright contempt.

In no other commercial field – medicine or plumbing or electrical contracting come to mind – are novices encouraged to charge market prices while “learning as they go.” Each has an apprentice period, usually measured in years, where practitioners are on a firm leash before being let loose on the public.

The problem is magnified in our industry because – unlike kitchen contractors or plumbers or even trash collectors – our customers are often in no position to judge the quality of the results.

I find it distressing that translation in this highly complex technical age is still stuck in a training and apprentice time warp, much like physicians were in the 17th century – not yet scientific, not yet rigorous, still part of colleges of barbers and surgeons. Learn as you go!

This is terrible for our clients, just like 17th century physicians were terrible for patients, usually doing more harm than good.

The way forward

“Learn as you go” is foolish and terrible advice for newbie translators in the commercial market. It condones errors as professionally acceptable, gives novices permission to charge unwitting clients for all those mistakes and, worst of all, traps them in an echo chamber from which – without training, collaboration and constant review by expert colleagues – they can never escape.

The industry urgently needs a feedback mechanism, a hard one, for beginning translators and it must be in place for a long period of time – if we are to have a new generation of expert translators out there – in all fields of translation, down to the simplest texts – who can actually beat Google Translate rather than spend the rest of their careers making minor corrections to it.

Fascinating to hear about your background, Kevin!

Your perspectives are also fascinating, although I note the lack of a solution to the problem. The freelance nature of the industry and considerable time it takes to become something approaching good means that such an apprenticeship would be costly (either in terms of time or money, and suffered by the apprentice/mentor or both), plus some apprentices would simply never “get there”. What to do?

This is the solution the translation industry appears to have found: demand less money from less-experienced translators (assuming they are less skilled), and pay more to those with more experience (assuming they are more skilled). We all know how inaccurate these assumptions are, but that’s not the point I was making. The major issue here is that good translators lacking in confidence are open to exploitation, i.e. working for parties who are not paying them what their work is worth. The fact this is a market for lemons adds to the problem, meaning an overall downward pressure on rates.

What’s the solution working for me and many other colleagues? Differentiation. Training. Marketing. Networking. Showing my skills and charging professional rates to clients who still in many cases don’t know I really am worth it, but will at least hazard to guess that I am. (Okay, there are multiple exceptions here: like the fellow translators I have worked for, or the clients who know enough to know my work is accurate, or the clients who see the results from a marketing campaign on a balance sheet – but generally speaking, they can’t say for sure WHY I am good – contrary to your suggestion – they just realise I must be.)

What is a translation buyer to do? Or worse, what is a newbie translator to do?

I don’t have the answer to these. Maybe you do.

I’m with you, Rose. As a newbie translator, I too noticed the lack of a solution to a problem which I wouldn’t dream of denying.

I spent three months as an intern for a translation agency. This time frame isn’t meant to sound like a lot, because I realise that this is really very little experience; however, I was unpaid, and since it was a full-time internship, with rent and bills and food in the town I lived, these three months cost me over £1500 just to survive. The only reason I was able to do it at all is because I am lucky enough to have completed my degree in Scotland where I didn’t pay for my tuition, and because my parents were able to help me. How does this make me feel? Crappy. Because I know that there are others out there who are just as talented or more talented than I am, but who could not afford to go unpaid for this amount of time only to get three months’ experience.

From what I’ve seen, newbie translators do not charge the same rates as experienced translators. However, as one of those people charging lower rates, I feel like I’m facing fire from both sides: on the one hand, agencies and other translators in posts like these tell me I have no right to charge what others are charging because of my lack of experience (despite my positive track record and stellar feedback from agencies and clients); and on the other hand, other translators complain that people like me charging low rates undermine the value of the business.

I know that many people ‘end up’ in translation after completing degrees in engineering or medicine etc. and I’m sure they make a very rare kind of translator which I could never be. However, some of us start out knowing we want to translate, and working as hard as we can to make sure we do it well. I know for sure that I couldn’t even afford another three months as an intern – and I wouldn’t want to, because I know that working for free or working for low rates is a ‘privilege’ not everyone can afford.

If I find a mentor who is willing to coach me, edit my work and agonise over every detail of my translations, without taking a substantial cut of my already small rate, then I’ll jump at the chance. But I need to get by somehow too, and my value is not negligible, which means I deserve to be paid a living wage for a task that not just anyone can do. No, I don’t expect to be paid as much as someone with all the experience described here. But there isn’t exactly a horde of veterans offering their services as mentors and coaches, and I think the best thing to improve the quality of young translators is less criticism (‘you’re charging more than you’re worth;’ ‘you’re charging so little that the trade is devalued’) and more support.

Don’t get me wrong, I do agree with the point of this article. But we’re not skydivers. It’s not a case of surviving or meeting a painful end. There are terrible translations that should never be read, never mind paid for, and those are not mine.

I may not have years of experience, but I am a good translator, and I will get better with experience. But I can’t work for free any longer, so now the only way for me to get experience is by working. And my work is worth a great deal more than a smashed-up corpse on a pavement. I know because my agency and my clients have told me so.

Hi Megan,

Thank you for your very thoughtful and heartfelt reply.

You’ve raised several important points and questions, so I’m going to try to sort them out a bit to get some clarity on answers.

First, what I’ve found personally useful in looking at the strength (or weakness) of my own skills over the life of my career is to see them in historical context. And the best way to do that is to engage in a few thought experiments. So bear with me a bit on this.

Imagine for a moment that you could jump in a time machine and go 25 years into the future. Assume you are a translator working at that time, too. But in the intervening 25 years you’ve finished a master’s degree in fine arts, completed several online courses on technology, built a few radio kits, collaborated with a dozen colleagues on the translation of a collection of menus and cookbooks, learned to fly small aircraft and published 10 books in translation on IT and mechanics, all through heavy collaboration with expert translators and editors.

From that vantage point, looking back at your translations today, you would be unlikely to see them with the same kind eyes that your current agency and clients do. In all likelihood — this happens to us all — you would be horrified by what you were producing when you were younger and less experienced in the world.

The market you are competing in today includes both the “young you” and a whole lot of “older yous.” The older version of you would probably snicker a bit and say that you would be lucky to be paid anything at all given the very young skill set you are currently deploying in the market.

The way to get from the “young you” to the “older you” is obviously to translate a lot. But your success is more dependent on your LEARNING a lot about the WORLD ITSELF, so the MFA degree, the online courses, the radio kits, the menus and cookbooks translations, learning to fly the aircraft, etc. (all of which I just choice arbitrarily for illustrative purposes) are hugely important to your ability to become a successful translator.

But first and foremost is having an expert colleague watching over your shoulder.

Elsewhere on this blog I’ve written about the crucial importance of collaboration to success as a professional translator. See especially, “Three Lessons: Humility, Collaboration, Perseverance.” I spend some time in that post discussing how I traveled that path myself, and how shocking it was to see how uneven (and appallingly poor) much of the work was out there in the commercial translation market by people who had skipped the collaboration stage altogether.

Nobody ever outgrows the need to be supervised.

Right now I am working on an encyclopedia-length book in an advanced scientific field that is recognized to be the bible in a highly sensitive field of physics. It’s a field I’ve worked in every day for the last 15 years — in collaboration with colleagues, from whom I’ve learned a lifetime of knowledge — and I’ve published 34 translated books in that field or related ones (see the “Publications” tab on the website where this blog is hosted.)

Is my work on this book being reviewed? Of course it is. By a team of world-class physicists. And they correct me, usually 3 or 5 corrections every 20 pages or so. You know why? Because I screwed up. I made mistakes.

The world is a complicated place. None of us gets better than reality.

My best advice for you is to find an experienced colleague or two or three and ask (beg) them to review and revise you. When I was young and going through the longest and toughest period of growth, about 10 years long, I was being paid 3 cents a word for my work as it was being re-written and revised and corrected.

It was the best investment of my life.

Good luck to you! And thanks again for being so straightforward and honest in your comments.

Hi Rose, I agree that the apprenticeship would be costly, but I’m not sure that’s a good reason for rejecting it. (For example, if you’ve ever watched humans endure medical training in the U.S. you’d wonder how such an inhumane system is even legal.) In the case of translation, if we know such a system rigorously filters out pretenders while reliably training up highly skilled translators, enormous benefits would accrue to those who withstood the system (as in the U.S. medical example) so you might be surprised by the number of people who might embrace it.

It would certainly minimize the number of graduates from translation training programs who either flounder in the market or become project managers instead of translators (this happens a lot in the U.S.).

The way the boutique market handles this right now is through careful recruiting and training — mostly screening for “what you know about the world” knowledge and long-term solid translation experience under the eye of somebody you trust — along with loads of feedback. I built an entire company on this principle.

I would like to see the more visible and publicly vocal translators embrace collaboration and review by their own respected colleagues as an essential factor of best practices. Chris Durban is too much of a lone voice on this topic even though she’s absolutely right. Yes, differentiation, training, marketing and networking are all important, but they are not exercising the cognitive muscles to stretch a translator in unfamiliar and necessary ways. The cognitive trap of confirmation bias alone can be disabling, especially when nobody is looking over your shoulder to point it out.

I think it would be helpful to come up with some sort of Red Ink Rule as a guideline to point people in the right direction. Hands-on collaboration is the absolute foundation of every discipline where standards are respected, especially science, engineering and technology. We need to push translation in this direction.

Thanks so much for your comments!

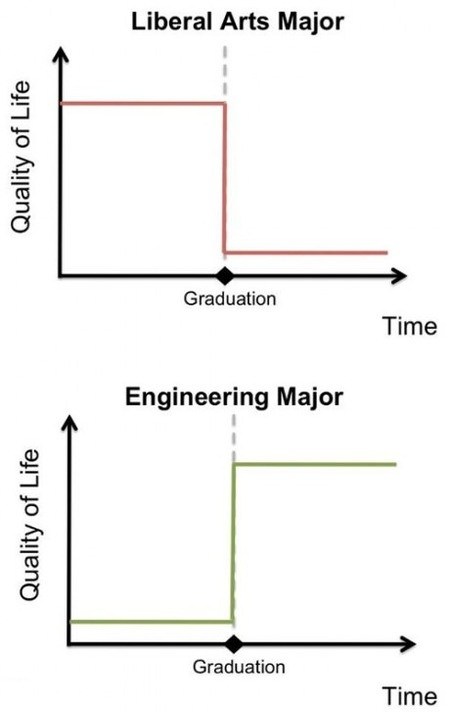

Kevin, I’m not quite sure how your “quality of life” chart fits this particular essay, but I was pleased to share it with a young lady who abandoned her university language studies and is now punching her way through the last year of an undergraduate program in electrical engineering. I told her ages ago that if she really wanted to be a good translator in technical disciplines she should spend a few decades working in them first. It is a dangerous myth that dictionaries, Internet access and a few nerdy acquaintances are all one needs to handle trivial subjects like medical device operation or chemical safety, but one sees the Dunning-Kruger effect at work every day in our profession. A good number of those asking simple questions about a point of science or engineering lack even the basic educational framework to understand the answers or to recognize how many points they have “understood” mean something very different. Your skydiving analogy is a little inaccurate here, because with translation under these circumstances, it’s the reader getting pushed out of the plane. Sometimes without parachute.

Given the pervasive promotion of unprofessional practices by the large linguistic sausage factories or even the general ignorance of the public in matters of language, I think any call to better behavior which is not backed by a sharp, naked edge of penalty has little chance of success. However, remedy in the form of new liability laws aimed at the deepest pockets and a generation of motivated legal sharks swimming in our waters might introduce enough of the necessary fear where it matters. I would hope that liability would extend beyond just translators, translation brokers and careless translation buyers but also include any and all parties involved in the exploitative engineering of machine pseudo-translation and post-processing. Drive a message of real legal liability like a stake of holly through the heart and maybe you can kill the monster.

The past decade and a half have seen a considerable deprofessionalization of translation in many areas, and this has not been driven for the most part by translators and wannabe translators however ill-advised some of their personal decisions may be. The situation years ago, where a novice might have the opportunity of secure employment in a communications department of an engineering company, surrounded by experienced professionals to guide them in many of the relevant disciplines, is unfortunately too rare now. If we want to go beyond the rare, happy exceptions of second-career translators who know what a circuit is and how it works, the effort to get there will require measures that corporations and governments probably lack the wisdom and resolve to take.

Kevin, the “quality of life” chart was, I confess, rather inelegantly stuck in right under the section of text explaining why knowledge of the world is important. I should have spent more time talking about the changes we need to make in training translators and interpreters. That’s a separate blog post and conversation, but I do think we need to move translation training programs a million miles away from the foreign language departments and start recruiting from the engineering, law and science departments in universities where people actually learn things.

You and I both know that this is the reality on the market, anyway. New translators with solid technical skills slip effortlessly into their new translation careers, while newbie generalists armed with mostly useless advanced translation degrees struggle or simply drop out of the market. This trend will accelerate.

We looked at liability as a key driver in ATA PR and it’s why the messaging we used focused on the downside of using non-professionals — we were pushing fear everywhere. I agree that it would be gratifying to see plaintiff’s attorneys chasing unscrupulous LSPs out of the business, but as many have noted — you among others — those LSPs already shun liability for every aspect of their product right now, anyway. At the extreme, it’s sort of amusing to watch the Dance of Liability Disclaimers when it comes to the TAUS MT lovefest, for example.

The flip side of liability and loss is profit and growth. Right now the market corrects for these inequalities by rewarding those who risk their own money to leverage the talent in the right way and I’d be the first to say I benefited enormously by spotting the gulf and building a company — and paying well — those translators who came down on the right side of the experience-in-the-world equation. Most of the high-end boutique companies profit from the current imbalance and that money flows into the pockets of translators who have real skills. So these folks with all the right skill sets and business acumen who are not fighting over a cent here and there are in no hurry to try to change this system. It’s unfortunate, because building out the model would expand work for everybody in this sweet spot.

I agree that there are fewer easy opportunities for collaboration and training in today’s market, but I think we’ve allowed the status quo of lone wolves to get way, way out of hand. In the direct client market the collaborative model is alive and well and there’s no reason it should not be extended into the “upper middle class” of translation where it might sprout roots and grow.

Thanks for taking the time to respond in such detail.

Ask to be reviewed for at least eight years (and beyond depending on the context) and include that cost in you rates. Network with colleagues and ask “Where to find” questions. Spend some years – 2 or 3 – in an agency environment and most of all, never stop opening up to new research tools, readings, experiences, etc. After about 15 years of rowing the seas of the translation world, I can now decently say that I am “seasoned”, and I do choose my fields and clients. As a result of all the years of hard work and humility, I can confidently say that I love my profession and enjoy waking up in the morning knowing what is waiting for me as the day rises.

Thank you as always, Kevin, for your enlightening article.

Excellently and very poignantly written, as always, Kevin!

This was a great pleasure to read. You truly are an extraordinary writer, who has an incredible knack for conveying more in a couple of words than most can in an entire blog or book.

I realize I say this about quite a few of your posts, but once again, I think it’s important to note that this “learn as you go” approach applies to more than just the translation industry. Probably most people who are currently employed, rendering services to others, can learn at least a pearl or two of genuine wisdom here. Personally, as an editor, I am in a constant process of learning new guides, styles, etc., and I am acutely familiar with the notion that confidence can be a very detrimental quality to possess.

Not only is it disingenuous and inexcusable for one to charge another for a shoddy job, it’s simply a disservice not to do one’s due diligence for every single project/assignment/etc. he or she takes on.

Rose, above, commented that you didn’t pose a solution to the “learn as you go” problem, but I respectfully disagree. You very pointedly state that one should:

“drill 100 miles deeper into your subject-matter expertise every single year, to seek out feedback and guidance and training, to collaborate and consult with your expert translator colleagues, and to revise and rethink and rewrite, and then to tear it all up and start all over again.”

It’s this process that, when done repeatedly over a long period of time, makes one at expert at what he or she does.

Is there an immediate solution to the problem? Probably not. If there were, anyone could call him or herself an expert. There’s a reason that there are particularly eminent people in each field.

I think just one of many important take-aways here is that everyone should be aware that these tiers of expertise exist.

Thanks as always for an essay that is both entertaining and though-provoking.

One thing that continually surprises me in the translation field is how seldom clients provide feedback to translators, in any form. This is the case even when the client has engaged an independent editor/proofreader to go over the text. I suppose that the agency is trying to avoid the catfights that can break out when translators dispute the best wording…but I try to always be gracious, even when pushing back against the corrector, and I always thank an agency profusely for providing me feedback.

I much prefer to have someone thoroughly review my work (rather than just the cursory glance of an English-only project manager). Increasingly, I am tending towards agencies that provide that, and when I can, I take on joint projects with a colleague where we can edit each other.

I do agree that specialization is essential, and the more practical experience one brings to bear on the subject, the better. The years I spent working in a research firm specializing in biological defense have been invaluable to the quality of my medical and pharmaceutical translations…likewise the life experiences of working in a pharmacy as a teenager, and having numerous close relatives with various diseases.

That said, though, I don’t think that it is practicable for every translator to reach your level, or even my level, of subject-matter expertise. For many of us there is not sufficient work in a single, relatively narrow subject area to sustain our entire careers. I specialize in medical/pharmaceutical translation, but that still is hugely broad. A presenter at the recent ATA conference, an internal medicine physician who also translates, said he – a doctor! – frequently cannot answer medical questions posed by his translator colleagues because they are outside of his medical specialty. The ideal, really, is your current situation: knowledgeable, specialized translator backed up by subject-matter experts. No translator can know everything about everything, or even everything about anything. We are doing very well if we just know what we don’t know.

I think it is also important to bear in mind the purpose of a translation. Different translations require different levels of expertise and different translation quality. Much of the pharmaceutical stuff I translate is incredibly straightforward: add 5 ml of this solution to 1 g pulverized tablet powder, blah blah blah. Yes, the translation needs to be accurate, and there is a little bit of jargon and industry-specific phraseology, but there is not much nuance there. Sodium chloride is sodium chloride. In contrast, a medical records excerpt requires a higher quality; instructions on the operation of a particular piece of medical equipment, still higher. Part of being a translator (and part of being a good translation agency, too), is knowing when you can get away with less experience and when you need more.

To some extent, learning on the job is inevitable, because none of us can afford to work with no pay or at apprenticeship rates for years on end. But it’s important to manage that process properly, minimizing the risk for the end user of the translation.

Hi Jen,

Yes, I agree that too few agencies provide feedback at all. It’s been a troubling development that’s accelerated in recent years and it ultimately is costly to both the agency and the freelancers — the agency is almost always just skipping the review process, which means their product is likely sub-par, and the translators learn nothing new, and, worse, are often encouraged to think their translations are flawless, e.g. are at a level that requires no feedback.

I would also suggest that translators working at the top of their fields ARE subject-matter experts. I’ve been mistaken for a working physicist at more technical conferences than I can count, largely on the strength of questions or observations I make about papers and presentations, up to and including people being quite adamant that I am playing a prank on them.

It’s not possible to produce truly authoritative translations in the scientific publication environment without having a very strong conceptual grasp on the ideas conveyed in the text.

It’s true that sodium chloride is just sodium chloride but what happens when you encounter, say “выделение” in a chemical text and you need to know a good deal of process to know whether a product or gas is being liberated, precipitated out of solution, deposited in solid form, visible at a particular transition point on a curve, etc.

The one area I’m afraid we disagree is about whether learning on the job is “inevitable.” It’s not. One can work under other experienced and talented colleagues earning much less (3 cents a word), as I did for over 10 years. I had to work much harder to make a living (much, MUCH harder) and use dictation to produce at a sufficient output to even make it feasible. But the results from that experience were profound. It allowed me to authoritatively evaluate other translators’ work based on millions of words of both mine and other’s translated and reviewed work. If this practice were more widespread — and I’m hardly the only one who went through it as I know many others who did and they are astonishingly good translators — there would be universal agreement about how crucial it really is and there would be correspondingly fewer attempts to explain how it’s not feasible because of (fill in reason translator did not do it). This is obviously not directed at you personally, but it’s the universal response I see when we get into these discussions.

Thanks again for your comments.

I went through much the same pipeline that Kevin did—at first, I only got detailed editorial feedback from two of the journals I translated; later, I had the terrifying experience of having my translations reviewed by the authors themselves, who were often *very* well-known in their fields. Some clients provided no feedback, but in those cases I had to be willing to always entertain the idea that any given sentence could probably be improved, and be rigorously honest with myself about how well the text flowed (I still made mistakes, I’m sure, but I think the editors caught the worst of them).

Dictation proved to be impossible for me until the visual feedback provided by modern dictation software became available, but in hindsight, that three-to-five year period really put me on the right path at a price comparable to what I might have paid for an MA in translation from Monterey.

Kevin, I’m a bit late to the party, but I was just pointed to this post and really enjoyed it. It makes me think of an experience I had back when I was teaching that I think ended up being a really good thing.

I had just moved to St. Petersburg to teach English for a few months, and was at my first or second lesson with my first student. Nobody had given me any training before I signed up for that program, and I just started teaching through the book the student was using at school. A few minutes in, while teaching something about present perfect, she slowly stopped me and tentatively remarked, “Jared, I don’t think that’s right.” My first response (internally, thankfully) was indignation, though a second look showed me she was right. It was a fast, effective smack in the face that taught me to keep a humble attitude, чтобы лицом в грязь не ударить.

I do have some questions, if you don’t mind. I would love to collaborate with other translators in the interests of building my skills and providing a better end product for clients, but I’m not even sure how to go about doing that. Do I look for someone at my experience or skill level so as not to be a drag on them? Is collaboration a normal practice? What about finding appropriate projects after you have a team in place? Or is that getting the cart before the horse, where you first find projects and only then look for a partner? I am sick and tired of the hamster wheel that is competition based on speed and price with a little quality thrown in, a wheel I realized recently I’d gotten dangerously close to, and this year committed to competing solely based on quality. However, I’m already a bit nervous about moving into unknown territory where I haven’t shown myself I’m capable of making enough to keep a roof over my head (I’m completely redoing all my marketing, branding, and even a good bit of my translation process) – can one afford to split profits with someone else and still make a living?

Thanks again for writing something I wish I’d read back when you first posted it. I am also focusing this year on surrounding myself with people more advanced, ambitious, experienced, and just plain “more” than me, and I will certainly be exploring your blog further to that end. It’s an added bonus that I can learn from someone in my language pair!