Professional-Quality Translation at Light Speed: Why Voice Recognition May Well be the Most Disruptive Translation Technology You’ve Never Heard of.

September 3, 2013

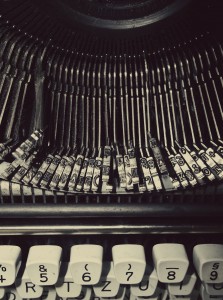

I’m sort of amazed translators working into English today still type out their translations on keyboards. Hunched over for endless hours at a time, day after day, banging away on an electronic version of a 19th century invention – a barely improved technology from Gutenberg’s movable type of the 15th century – all the while straining their fingers, eyes, wrists, back and weary souls.

It’s slow. It’s tedious. It’s exhausting.

It’s also why translator productivity keeps banging its head up against that relentlessly stubborn 2,000 – 3,000 words-per-day concrete ceiling.

It’s about time to ask ourselves this: Why are we translators in the 21st century caught in a typing trap? Human speech is five to seven times faster; cognitive processing about ten to fifteen times faster. Our translating brains actually work closer to these speeds – something any simultaneous interpreter can tell you – not at the interminable slog rate imposed by the need to pound out individual letters one by one on a keyboard.

Voice-recognition: It almost seems like magic

Modern voice-recognition technology in English, on the other hand, has finally matured in speed and accuracy to the point where you can’t even talk faster than the computer can process your voice and turn it into text on the page. Believe me, I’ve tried. On several occasions recently I’ve attempted, just for fun, to outrun my English voice-recognition software (Dragon Naturally Speaking Professional Edition 11.5) by reading as fast as humanly possible from a finished text. I can’t do it. The computer always keeps up with me.

It’s blisteringly fast, it’s always available, it never gets tired, it’s scarily accurate and the translation quality is professional human quality.

OK, that last part is me. But still.

Voice recognition today enables professional-quality translation at light speed.

A Professional Translator’s Dream

Voice recognition is a professional translator’s dream. The translator simply “speaks” the translation out loud into a headset microphone and lets the computer handle transcription, control and navigation. So the translator is essentially recording a sight translation. Here are some of the many advantages of voice recognition in translation:

• Improved translation quality and stylistic voice. You can radically improve your ability to “stay in the moment” with the text in the conceptual cognitive process without any kind of physical distraction. Vocalizing the translation for me consistently improves the stylistic quality of the target English text because it adds my ear as an additional aural filter. Speaking the translation out loud also blocks source-language interference and inelegant constructions in my mind.

• You are freed from the time lag imposed by the keyboard. Even though I’m a reasonably accomplished touch typist (70 – 90 wpm) the physical act of typing and jumping back and forth with my eyes from source document to target computer screen – or even within text and dialog boxes on screen when using TM tools – has always been very costly to my thought process.

• You are no longer slave to the plodding, strenuous and unnecessary strains of typing. By that I mean not just fatigue and potential injury to fingers, wrists, neck and back in the long run, but the cost of physical exertion and posture distortion – and sitting for hours – every single work day. By contrast the only equipment I use in dictation is a very thin, lightweight digital headset that I sometimes forget I even have on.

• Voice recognition allows you to automate every interaction you have with your computer and still work with TM tools. So you can still use all the tricks and shortcuts and macros and TM tools you use now, and you can also edit and revise text, but now you just say them out loud instead of type them and the computer executes them for you automatically.

• You can make a lot more money. Actually that’s a bit of an understatement. An accomplished dictating translator working in a very familiar field can produce 1,500 – 3,000 words per hour. Yes, you read that correctly. Per hour. It’s a draft translation (to be sure) and you will still need to revise it (always). But by using dictation you can increase your output – and your income – by around fourfold. This is one of the very many reasons that dictating translators very rarely complain about their incomes.

Caveats and Cautions

I’ve long proselytized on the virtues of dictation, dating all the way back to the Cretaceous Period of the 1980s when I began with an old cassette tape dictation machine and two full-time technical typists.

The first day I began dictating translations in the 1980s I almost couldn’t believe how much easier it was. I finished an 8-hour job in about an hour and a half and I just sat there, sort of stunned. I wasn’t quite sure what to do with the rest of my day.

In the late 1990s when I was running workshops and training seminars at ATA conferences, translators coined the term “Hendzel Unit” as a kind of shorthand to refer to my 10,000-word-per day production level by dictation in scientific and technical translation. So I’ve been at this for a long time.

It turned out that this approach came with some caveats, though.

• High-output dictation only works in fields and language pairs you know exceedingly well. I could dictate science and technology in a flash, but I’d worked hard to develop the subject-area expertise and translation skills in those areas. When I expanded into legal and financial translations later in the 1990s, for example, I was dismayed to find that I simply couldn’t dictate those texts. It took nearly five years before I had the subject expertise and familiarity to do it with ease.

Since dictation is a way to connect your mind to the page faster, your mind and voice need to be faster than your typing fingers are. If your mind does not work quickly enough in a given language direction or subject area, there will be no real benefit.

• You may need a bit of interpreter DNA nested into your genetic code to verbalize translations. Humans process spoken language and written language through different cognitive processes – even different pathways in the brain – so those areas need to be able to talk to one another. But most dictating translators I know are not working interpreters, so perhaps only a bit of that DNA is all that’s required.

• Professional-quality voice-recognition software must be available in your target language. This is a major stumbling block for some translators, as are the limits on the ability of English-language software to recognize certain forms of accented English. You can still hire typists to transcribe your dictation, but voice-recognition by definition is dependent on the availability of suitable software.

• Dictated translations are still drafts that require revision and editing. As you develop and refine your dictation skills you will reduce the volume of editing required, but it’s important to recognize that dictation is never a substitute for text revision and polishing.

• Higher-end computer hardware is required. Voice recognition software runs best on very fast processors with as much RAM as you can get – 16 GB is a great start – with a solid-state hard drive (ssd) ideal. This hardware configuration has only recently become reasonably affordable, but do expect to pay a bit more for hardware than is required for other applications.

The poor stepchild of translation technologies

Voice recognition has remained in the shadows as a translation technology principally because there’s nobody out there – beside the individual translators – who reap the enormous financial benefits from its use. In other words, there’s no immediate or ongoing financial benefit to anybody else along the translation food chain other than the translator.

By that I mean that in the TM and MT technology market, unfortunately, it seems that there’s always some non-translator with a hand in your pocket trying to sell you a platform or a tool or a technology where some of the ultimate cost benefit goes to your customer and not you. Not so with dictation.

Turn the per-word market to your advantage

Your mileage, as they say, may vary. But dictation is worth considering, especially when discussions of translator income seem unnecessarily focused on per-word or per-hour rates instead of on total output and productivity, especially in the case of dictation, where the productivity improvement remains 100% in the translator’s pocket.

So if the market insists that you be paid by the word, take advantage of that. Leverage technology and your own skills to deliver, on a regular basis, a dramatically larger volume of high-quality words.

Your bank account – and your weary fingers – will thank you for it.

Very interesting piece, Kevin. I have idly considered this option myself without ever exploring it. Your piece isn’t designed to push any particular software, I notice, but I would personally be interested in knowing which speech to text package(s) you were using, and whether or not the onboard mac option, for example, was of good enough quality.

Many thanks

Duncan

I use Dragon Naturally Speaking Professional v. 11.5. The “Professional” package is important as it contains a dramatically larger lexicon. I’ve not used the voice recognition that comes with Macs, so I can’t speak to that option, sorry.

Your article looks highly interesting. However, my experience with a) Dragon Naturally Speaking (v. 7) and b) Windows Speech Recognition leads me to conclude that manually typing in is more effective and far less frustrating!

Stephen, you may want to check out what the current generation of voice-recognition software can produce (your Dragon v. 7 is 5 versions behind the most recent release, which is 12.0). I have posted a test using Dragon v. 11.5 in response to Catharine’s comments above.

Interesting article, but I remain to be convinced. I’ve always found that I can type faster than I can dictate – even if the dictation involves speaking a previously written text. I’ve found that the need to articulate and ‘speak’ punctuation makes it a slower process (for me) than typing.

Hi Catharine, I ran a timed test just now that consisted of my reading text from one of my published book translations. The following is from “Laser Optoacoustics,” American Institute of Physics (1992) dictated using Dragon Naturally Speaking Professional v. 11.5. This is exactly what the software generated — this is unedited — in exactly one minute:

Both an acoustic wideband pulse and thermal lattice vibrations can be resolved in the plane waves. The specific nature of the latter lies in the fact that thermal vibrations are chaotic vibrations. In this case, chaotic refers to the fact that with a large number of ways responsible for thermal motion of the medium, we cannot identify their phase variations. This is due to the fact that even a weak interactions between isolated waves when there is a large number of ways causes rapid initiation of chaos of the phases of the individual vibrations, although there may be slow changes in vibration amplitude. It is therefore possible to attempt to simplify the description of lattice thermal vibrations by using statistical averaging (averaging over the phases). Indeed, such an approach makes it possible to obtain a kinetic equation for acoustic noise without employing the apparatus of quantum mechanics.

This is 147 words in one minute, so if you can type 147 words a minute, you can beat the machine!

The dictation is not perfect — here are the three errors:

“in the plane waves” should be -> “into plane waves”

“a weak interactions” should be -> “a weak interaction”

“with a large number of ways” should be -> “with a large number of waves”

Otherwise, the text is good to go.

You may find that by training the software to your voice, accent, cadence and word usage it will run pretty much as fast as you want it to.

Thanks for the mention of this article on Twitter, I appreciate it.

I tried typing and then dictating your text above. My dictation software is not Dragon, but the inbuilt Mac software available with Mountain Lion.

With typing I only did 40 words in a minute – this is rather slow as I correct myself as I go along.

With dictation the software stopped after “their phase variations.” (which it actually wrote as “their phrase variation” – the only mistake). I then started dictating again and reached as far as “vibration amplitude” in one minute, however there must have been too many things the software didn’t understand in the second part as it refused to write any of it – this is something frustrating I’ve noticed with the Mac software, I don’t know if it happens with Dragon too.

So with dictation software I reached 60 words in a minute compared to 40 words with typing, however the dictated text had errors and I would have the frustration of having to repeat myself dictating the second part of the text.

Maybe I gave up too soon on training my dictation software; your article has convinced me to persevere and perhaps give it another go!

Interesting. It does seem that the Mac software may be your weak link. I’m a big believer in training the software, but I wonder if the lexicon is large or robust enough in the Mac program to handle professional translation.

The DNS Professional version 11.5 I’m running is a professional tool and it’s priced like one – $599 when I bought it in 2011 (it’s since dropped a bit). What might make better sense for you is to try out the regular DNS office version which is much less expensive and see if by training it you can at least double or triple your current performance.

I completeley agree with you, Kevin. I’m using DNS for 3 years now (current version 12, Pro) and it has delivered exciting results. Even if, sometimes, it gives amazing results, but, most of the time, it is my fault : bad position of the microphone…;o)

Thank you for this one, Kevin. When I’ve made some of these points in discussions of the wonders of MT with post-editing, the silence in response is deafening.

Among the caveats, I would also note that heavy tagging of texts will slow you down considerably, which is another reason why I insist that tags be included in piece rate counting methods for translation costing. But voice recognition can still give you a comfortable 3000 word output on a day which might otherwise be grueling, with well under 1500 words at its end.

When I first mentioned my observations of a legal translator with a output of over 10,000 words/day, one agency owner I know wasn’t surprised at all. He said that was typical of the older translators who dictated when he began his career decades ago, but at the time, the wait for turnaround from a typist was a limiting factor that finally led translators typing in a word processor to dominate.

But with automated transcription, alignment and options for subsequent QA, there is really very little you can’t do with voice recognition.

Hi Kevin, I agree with you on the tagging issue. With respect to the deafening silence from the MT folks, perhaps the best way is to use metrics that employ currency notation instead of purported “accuracy” data. In that respect, a better title for this article may have been, “Getting it Right the First Time: Could High-Speed Professional Voice-Recognition Technology Challenge MT?”

Kevin —

Your comment about auto-alignment capability is key to the way that translation fits into the larger multi-lingual content management workflow. Our business models and even industry jargon have failed to keep up with the changing role of “translation” in our modern world. My early days in translation (pen and paper not dictaphone) were all done and paid for by the reader who desired access to (for example) professional journals published elsewhere. These days free MT provides a good starting point for individuals with that need (despite its relatively poor quality), but for higher-value usage the kind of dictation discussed here is perfect. However, the cast majority of translation these days is paid for by the content generator (as localization), and the translation itself is a rather small (though essential) part of the overall multi-lingual content management effort. In this context, the value being paid for includes both the translation itself and the associated tagging and alignment that allows the finished work to be taken under management in some content management or publishing system where it can be used as leverage for future versions of the same base document. I think that translators who adopt this kind of “personal technology” approach can still provide value and generate acceptable income in the localization workflow, but you need to remember that your customer is solving a bigger problem than “translation”.

Bob — Yes, thanks. Two points.

I spent 18 years in the localization trenches myself — developing workflows, QA processes and even (gasp!) selling localization services — back when I owned and ran ASET so I’m well aware of the content management aspects that come into play in many sectors of the translation-services industry.

It occurs to me that some of the key advantages of VR technology today, such as the ability of such systems to execute navigation, correction and document handling functions, could easily be targeted at other tasks to allow the voiced translation to be integrated more efficiently into various workflows.

I also think there is a distinct advantage even today to “getting it right the first time” rather than buy into MT systems where errors constitute an inbuilt functionality.

My other observation is that we all tend to think of the “translation industry” as constituting whatever we have done or are doing right now. I believe this is a mistake. Yes, the localization of right-now-everywhere-immediately-available web content is an important and growing sector, but there are also the high-quality (and high-profit) sectors of prestige marketing, corporate legal and regulatory, finance and compliance (especially), and publication-quality science and engineering, to name just a few, all of which are distinctly zero-error environments and all of which pay a premium for getting it right the first time.

I was born 30 years too soon. If this capability had been available when I was a full time dictating translator (I left the field in 1990) I would probably still be doing it (assuming work to be available). The years of dealing with typists, audio cassettes, and endless proofreading and editing would recede to a distant memory (but pasteup of graphics in some form – no doubt digital – would still be necessary).

Hi Dave, so glad to see you here! Just so people reading this know, Dave Moore was instrumental in inspiring me to dictate back in the Cretaceous Period I mentioned in my blog post.

You can see from the test I posted elsewhere that the software is pretty sophisticated these days and the mistakes it makes are often the same mistakes a very skilled typist might make.

I appreciate your taking the time to comment.

I consider myself a dictating translator, but I can’t translate 1500-3000 words per hour from Russian to English in my specialty — international relations and foreign policy. The time needed for research is simply too great. Take personal names, for example. Russian writers spell foreign names phonetically. Finding the proper non-Cyrillic spelling of a Chinese, Korean, Arabic, French, Dutch, etc. personal name can take a considerable amount of time, especially if the person named isn’t an international figure.

That said, however, my output definitely soared when I began using a speech recognition program. What it usually means in practice is that I finish a day’s work before noon, have a leisurely lunch, do something else for a couple of hours, then check what I have dictated. If I don’t do that, my eyes slide right over mistakes. Remember, even with a 99% dictation accuracy, Dragon mishears about one word in every hundred.

I first dictated translations back in the 1970s while working as a staff translator. The organization I worked for had hired a number of young, inexperienced typists and formed them into a typing pool. Their accuracy was far worse than that of Dragon. I once wrote a poem full of double entendres using mistakes made by a typist in an article I translated on metallurgy. When we translators got our hands on IBM Selectric typewriters, we considered that a step up. (Incidentally, my boss’s boss once saw us typing away and said to my boss: “Why don’t you get these guys some of those typewriters they talk into so they can just dictate their translations?”)

My figures of 1,500 – 3,000 words per hour are draft, not clean copy of course. I do most of my research before beginning dictation — I always have — so I that means I have a list of all the names with proper spellings, which in science and technology are usually well-known enough to be included in the software lexicon. In IR and foreign policy certainly you would need to correct things like proper names, obscure treaties, titles of minor public figures, crazy remote islands in the Arctic, etc., as the software would no doubt produce some bizarre renditions of those.

I also work from Russian into English and I’ve trained my software to recognize the names of people, institutes, cities and programs as I pronounce them as if I were speaking Russian. Yes, when dictating (but not in regular daily speech) I do that sort of annoying thing people sometimes do where they mis-pronounce foreign place names in English by vocalizing them as though they were speaking the respective foreign language. The software doesn’t care — it just maps the crazy phonemes I say out loud back to the spelling I tell it to use and everybody is happy.

Thanks for your comments.

Of course, if you are researching names and other terminology before you begin the actual translation, it means that you are spending extra time pre-reading the text. This could be a significant amount of time depending on the length and complexity of the source text. I suspect that most translators never fully read the source text before they start translating in order to save time. When assessing whether I want to accept an assignment, I usually will only skim read the text (meaning I read the first sentence of each paragraph) in order to judge whether I can take it or not.

My experience is quite different. I would certainly never accept a text after reading just the first sentence of each paragraph. That’s not only inviting trouble, it’s actually AGREEING to accept the risk of being unqualified to do the text, or to translate it competently within the time limits you’ve agreed to.

And of course, the first step in any translation assignment is not only to read through the text carefully, it’s to research all the terminology cited in the references by the authors and validate terminology and usage before beginning. What I mean by that is that you go read the scientific journal articles in English cited in the references of your text. I did this as a matter of course even in the Pre-Cambrian era when I was dictating using magnetic tapes and my transcriptionists had just begun using word processors.

… although the typist renditions I recall might still slip through: I recall such gems as “World’s seas and oceans” becoming “Worlds’ seasoned oceans “(salty, no doubt), and “towed chains of sensors” becoming “toad chains of censors”

I remember one of the worst typos from my high school journalism teacher: the headline “battle-scarred general retires” became “bottle-scarred general retires”

I think you may find many generals who would admit to you that that when scarred by the former, it’s not unusual to also become scarred by the latter. 🙂

I only wish Dragon would be available also for the Russian language one day, like Nuance announced a couple of years ago.

Thanks for another great post!

Real Speaker is available for Russian and several other languages. Have not tried it, just passing on the link…(мопед не мой…).

http://www.realspeaker.net/en/

I’m also not sure if the software could handle my very thick American accent in Russian.

A couple of questions, if anyone is able to answer them

Is Dragon the only option here? Or are other software packages available?

There seem to be various versions of the Dragon software. Are any of these more suitable for translation for any reason? Is the cheaper Home version good enough?

Thanks in advance

Duncan

Hi Duncan, I have given a seminar at each of the last two ATA conferences instructing translators on using and evaluating Dragon and also wrote an article for the ATA Chronicle on the subject. I found that there was and remains no suitable substitute for Nuance’s software; no other voice recognition software on the market would work with a CAT tool. Among the versions available (for Windows at least), Premium is worth the upgrade over home, because it more reliably works in different CAT tools and also offers the ability to add custom words, which is very valuable for a technical translator. Hope this helps.

Thanks, Andrew.

I am only able to speak to the DNS Professional system as that’s the one I use. In general my philosophy about tools — whether it be dictionaries or computers or software — is that if you’ve researched and selected your tools carefully, cost itself should not be a factor because the benefit — again, if you’ve weighed the options carefully — will far outweigh the cost.

Discussions on Twitter and LinkedIn today about this blog post have supported this — that the free or low-cost versions on Mac and PC perform at a much lower level and may make them unsuitable for professional use.

Having said that, I do believe that you could certainly test out the lower-end DNS software on your computer to see how dictation works for you and later upgrade to DNS Professional, which is costly but very much worth it.

I hope that helps.

Hi Kevin,

Thank you for the interesting article. This is timely for me as I have just purchased a new computer with the hardware to make this work. I have read that the microphone you use is crucial. Have you any recommendations?

Thanks again.

Stephen

Stephen, yes, the microphone is important. Any reasonably high-quality digital noise-cancelling mic with a USB connector would work well. I use this one: http://www.amazon.com/Andrea-Fidelity-Monaural-Computer-P-C1-1022300-1/dp/B00206WJ42/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1378321247&sr=8-1&keywords=Andrea+anti-noise+NC-181

I could be mistaken, but I think the main difference between the “professional” versions of Dragon and the “premium” one is the specialist recognition dictionaries. In any case, most of the people I know use the premium version with a decent microphone and train it to deal with their own specialist vocabulary. I tried to buy a “professional” version ages ago in Germany, but I never did find my way through the labyrinth to a supplier, so I just got the “premium” version off the shelf.

Here’s a good summary of the different functionality: http://www.ngtvoice.com/downloads/dns12-premium-vs-pro.pdf

Many thanks everyone for the very useful summaries. I don’t use MT or CAT tools at all in my work and don’t intend to, so perhaps it is less vital for me to have the Premium or Professional versions. Despite my luddite-and-proud tendencies, I still think this might be an option that speeds up some of my work . Cheers, Duncan

There is an SR_for_translators group on Yahoo groups that might be worth looking at. Despite the claims of MT vendors, it is definitely not the only game in town to boost productivity. I believe the Translation Process Research people at Copenhagen Business School are looking into ASR as a tool to boost productivity. It would be nice to see more of the same from the research community.

I think other translator training institutes should also look into giving their students an introduction to Dragon, at least for into-English translation. It would make an interesting topic for a questionnaire-based masters thesis in translation studies. I am not aware of any studies to date but I would be interested to hear of any.

Warm regards,

John Moran

Very useful article and exchange of opinions! I would like to test the SR approach, and I wonder if anyone can suggest the best way to go about it with low trial costs. (If it proves effective, of course, I’d be prepared to spend the necessary amounts on high-end hard- and software.)

I know, for instance, that there is a 30-day money back policy on DNS. But I currently use Trados Studio 2011 on a Mac using a VMWare Fusion virtual desktop. My Mac has only 8GB of memory and my main concern would be that this is too little to permit adequate testing. At the same time, I’m not too excited about the prospect of buying a new, cutting-edge computer only to find out that SR doesn’t work for me (fast typer, but developing wrist problems). Any opinions very much appreciated!

I am going nutty trying to get speech recognition (Windows 7 Premium Home) to work. Constant errors not matter how fast or slow I dictate. V always comes out as B. My cervical spine is narrowing, spurs, etc., and I have 2 compression fractures in my thoracic spine – meaning I had to stop bending down to see the keyboard. Is Dragon that much better? Thanks.

Yes, in my experience, Dragon is *much* better than the speech recognition that comes with Windows. Dragon seems to cater to a wider variety of English dialects rather than merely expecting some sort of standard speech pattern. For example, once your speech is classified as “r-dropping New England dialect,” the software then knows that it probably needs to deal with a whole bunch of other peculiarities.

For me, Dragon’s speech recognition became nearly perfect after dictating about 10 pages of text (the software trains itself as you dictate documents, so recognition continually gets better).

You do have to watch out a bit, even after recognition improves: The software is initially set up so that saying “period” enters a “.” rather than the word “period.”

3000 words an hour?! Hardly. I’ve been dictating translations for 15 years and my output is 3000 words a day. If indeed you can dictate 5 times faster than you can type, this suggests that when typing you would translate 5000 words a day. That’s just not sustainable for anything that isn’t so simple you might as well use a machine in the first place. Dictating is great, but the benefits are way overstated here. I would guess at a 20% increase in output, not 400%. Because the bulk of translation time is spent editing, not inputting.

Chris, I think you’ve seen from the comments here that the range of increase can vary dramatically based on experience, nature of the material, etc.

The first time I ever used dictation I tripled my output. But then, I was working on material that was intimately familiar to me, and was in a specific limited technical domain.

The same does not hold true with new or unfamiliar texts, which is why I had to “re-train” in certain disciplines later in my career before I could dictate in them.

I think there is value in listening to how a wide range of different professionals have found benefits in dictation, which includes how significant their productivity gains actually are.

Hi Kevin,

Thank you for this post. I read it with interest, as I am considering buying Dragon VR software. I have a few queries, tough, and I was wandering if you could help me:

1 – I translate both from Brazilian Portuguese into English and vice-versa. So which package would I need to buy in order to have both languages ?

2 – My English is near-native, but I still have an accent, and the bulk of my work is Port-Eng, simply due to market demand, so I am wondering how good would Dragon be in recognizing a foreign accent and if I can train it to understand me. I lived in England for a very long time 915 years) and the British had no trouble understanding me, but I am concerned if Dragon will.

3- Do you have to be on-line for the program to work?

4- Do you have to switch it off when you are researching terminology? I usually research as I translate and not beforehand, so there will be some silence for a while…

I would be really grateful if you know the answer to these questions, since there is no demo version to try it on before you buy.

Thank you.

Hello Eliana,

Thanks for your comments on the post. I’ll do my best to answer your questions (and welcome input from other commenters).

1. To the best of my knowledge, Nuance does not offer into-Portuguese as a language direction. You’d have to use it for Portuguese into English.

2. You can train the program to understand you, as it will prompt you on age, location, etc. as you set up the user profile. If you acquired a British accent in your 15 years in England, you may be best using that as the language setting (it offers both US and UK English).

3. The program is downloadable onto your computer, so no, it’s not required that you be online to work.

4. The headset/mic setup has a manual switch which you can use to turn off the recognition function at any time. It’s not unusual to turn it off repeatedly, even while dictating, as you formulate complete sentences in your head. You have the option of leaving it open and running, but any noise tends to trigger the software to generate words, and it’s best to simply pause it as needed. I would recommend that you buy a dedicated noise-cancelling microphone connected to the headset with a USB plug-in to your computer. The headset that comes with the program tends not to produce the best results.

Also, the better and faster your computer, the better your results — so at least a Quad 4 processor, 16 MB RAM, and a ssd (solid-state hard drive) can make a huge difference in your accuracy and speed.

You might also pose your questions on the “Translators Who Use Voice Recognition” group on Facebook if you are a FB user, as that’s an excellent venue to get the best and most updated results.

Hope that helps!

Kevin

P.S. Sorry, I meant “15” years, not “915”. I should be so lucky to live that long… 🙂