Confirmation Bias: Why Collaboration is the Path to Translators’ Best Work

November 29, 2012

A great pitfall in scientific research – and in everyday life – is the very human penchant to see what we want to see rather what is actually there. In psychology and cognitive science, this tendency to filter reality to bolster our own views, theories or explanations is called confirmation bias. It’s deadly in scientific research because it drives well-meaning and quite dedicated researchers to interpret evidence in a way that’s unwittingly partial to existing beliefs or theories, which skews results, blocks valid conclusions and often points in the wrong direction.

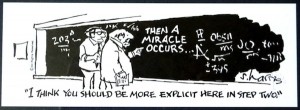

Confirmation bias also explains why we think our political views, for example, are self-evident to all rational people, and why those holding opposing views must be mistaken. In the extreme, political punditry in the U.S. owes its entire existence to confirmation bias. People seek out news, entertainment and commentary that support their particular viewpoint. It’s one reason why people on the losing side of the recent U.S. presidential election were so (genuinely) shocked by the outcome.

Frequency illusion

Then there is the frequency illusion in confirmation bias. Translators are very familiar with this phenomenon. It occurs when we first learn a new word or concept and then suddenly start seeing that word or concept in use everywhere (this also happens with popular songs, movie titles and obscure celebrity names, among other things). It’s not that any of these are more common, it’s just our reality-perception filters have changed. Where we once subtly ignored what we didn’t recognize, we now promote them in our mental RAM to stand out in stark contrast.

Experts are the worst

What’s even more troubling is that confirmation bias seems to get much worse with increasing level of expertise. The more prominent and confident the physician or attorney or plumber or cattle wrangler, the more persistent is their tendency to favor their existing beliefs over alternative explanations or new evidence or even paradigm changes. This goes a long way toward explaining Einstein’s absolute refusal to accept the quantum world in his lifetime, despite the saintly patience of Niels Bohr in attempting to persuade him.

Natural selection

Confirmation bias is a deep-wired and persistent behavioral response in humans that was selected for in a hostile world where there were profound survival advantages to making quick decisions based on familiarity (“familiar = safe”) at low biological cost.

It turns out that our minds are not wired to seek “truth,” or even objective accuracy.

Confirmation bias is an intrinsic, built-in feature of human thought and the only way out in science is through careful experimental design, rigorous statistical analysis and skilled peer review – peers outside your own bias bubble.

No rescue from rational thought

The psychologist David Perkins has determined in studies of gifted university students that while IQ was the most powerful indicator of a person’s ability to argue, it turns out that it only predicts that person’s ability to defend positions already held. It was a poor indicator of the ability to argue either side from facts. The emotional overruled the rational. Perkins found that “people invest their IQ in buttressing their own case rather than in exploring the entire issue more fully and evenhandedly.”

Research on confirmation bias conducted by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber, French cognitive scientists, validate this. They found that our evolutionary intrinsic biases and errors in reasoning destroyed any notion of objectivity in rational thought. “Skilled arguers are not after the truth, but after arguments supporting their views.”

Translation is largely intuitive, not rational

My point in beating up on rationality above was not to trash empirical analysis but to emphasize that there’s a great deal of evidence from psychology and cognitive science that humans are quite often emotional thinkers, not rational ones.

This is even more true of the craft of translation, which is a high-focus process of intense cognitive construction via a blizzard of decision-making. In a typical translation we make thousands of decisions, some visible and rational, but most invisible and highly intuitive.

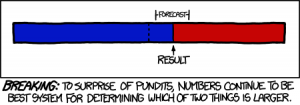

The process is so intuitive that we translators often have a very difficult time explaining to others exactly how we make all these conceptual choices and on what basis. This process has always reminded me of the famous Sidney Harris cartoon on physicists:

Translation as domain-hopping

What we translators do is map our understanding of a reality in one domain over into a completely different domain. Translation at its core goes well beyond manipulation of language symbolics – it’s really domain hopping, much like listening to an aria and then painting a picture to represent your understanding of what you’ve just heard.

So into this stew of deeply intuitive reasoning and rampant confirmation bias we mix the frank reality that most of us work alone. Massive electronic interconnectivity has mitigated this isolation to a significant degree, but that only works when translators seek out assistance from their peers on a regular basis.

This also requires that translators “know what they don’t know,” which is a bit of a logical paradox – if you don’t know something, how could you possibly be aware of not knowing it?

It’s easy to ask a question about a term or phrase or concept you doubt, but what if all those terms you are sure you know are….wrong? Or there’s a better, more concise, and elegant way to say them? How can any of us really improve in any meaningful way without constant, ongoing, direct and honest feedback from our peers?

Self-revision and confirmation bias

It’s also a truism that successful translators are their own worst critics. We revise and self-edit endlessly and can barely release a text from our clutches. If it weren’t for deadlines, we’d never finish a translation job.

What makes this situation a bit dicey is that even the most self-critical among us suffers from confirmation bias. It’s that little itch that we scratch when we find what we think is a perfect solution, only to recognize years later that it was in reality a B- or C+ solution and the A solution never even occurred to us at all.

The late Ben Teague and I used to swap stories on the old FLEFO translators’ forum about how much we deeply hated reading our old translations. This was why. With the benefit of greater experience and enough distance from the text to free us of confirmation bias, the stark reality of our blinding errors would jump right off the page.

Collaboration to the rescue

In group settings it’s far too much to ask of humans with their cognitively biased brains and deep self-image investment to be completely fair-minded, objective, straightforward and honest about their own translations when their reputation and self-interest are on the line. It’s too daunting for us to even see objectivity hiding in the weeds.

Our brains are simply not built that way.

The way around this dilemma is to invoke the wisdom of peers in a group setting. We are far more insightful and less burdened by self-image threats when examining the work of others. Key to the success of such efforts is to put everybody’s work up for collective review – this creates the safest environment where there’s a shared investment in a common objective.

This is why collaborative workshops at ATA conferences or Grant Hamilton’s recent “Translate in the Townships” event or hands-on regional workshops can feel both invigorating and refreshing. Wisdom becomes an emergent property, an entelechy, of the social group.

These same dynamics can be achieved through virtual collaboration, a practice I fear is in decline in today’s translation industry. At the top end of the translation market, though, collaboration is very nearly enshrined as a guiding principle of best practices.

And there is a very good reason for this. It works.

Kevin,

Excellent. Thoroughly excellent.

I like it, especially the part about hopping domains. Very thoughtful

This is an incredibly cogent, thoughtful, and thoroughly comprehensive exploration into confirmation bias — a term everyone should learn — that’s not only a very enjoyable read, but a MUST-read for translators and non-translators alike. Though it’s oriented toward translators, it discusses critical concepts of the human mind and how all of us interpret information from everyday life in relatable terms. Well-researched and creatively-written. Thank you for such an engaging and highly-relevant post!

Some excellent points. Thank you.

Excellent! Dreadfully accurate thoughts.

Being a translator for 2,5 years only, I’ve found a source of inspiration and motivation, Kevin. I’ve found your blog.

I’d like to say thank you for all of your articles.

Thank you for your kind words, Alex (or is it Sasha?).

Thank you. Still digesting this very pertinent article.

This dovetails nicely with a book I’ve been reading entitled “You are Not So Smart” by David McRaney. It’s all about the myriad ways in which our reasoning and memory are not nearly as logical and orderly as we like to think. He covers the two biases you mentioned – confirmation bias and the frequency illusion – as well as many others.

I feel like I have a good idea of the role collaboration played in your life as a translator, but I would be interested to hear about how you fostered collaboration as an agency owner.

Hi Jen, thanks for your comments. I suppose my first observation would be to challenge David McRaney on the title of his book. I think that humans are incredibly smart, but that a great deal of that intelligence is intuitive and relational and sensory — those fuzzy things selected for in a hostile evolutionary environment where we were at perpetual risk of starvation or isolation or death. So we are all the progeny of ancient forebears who were very good at making the right choices intuitively and very quickly.

The error I think lies in our modern bias to define “smart” in a narrow analytic sense, which I suppose is not surprising since we spend at least a dozen years of our early lives (and often more like 16 – 20) in classrooms being told that “smart” is what we faithfully regurgitate on the page.

I would strongly recommend Daniel Kahneman’s “Thinking, Fast and Slow” as essential reading to understand how our minds actually work.

To answer your question about how I fostered collaboration as an agency owner, here’s how I answered that question in a recent LinkedIn discussion:

Collaboration is a choice.

I ran the ASET Russian nuclear and legal translation programs as massive collaborative enterprises that incorporated expert input, feedback, training, glossary-development and review. That effort stretched across in-house and freelance translation pools in 12 time zones.

Much of the confidentiality limitations associated with that work went way, way beyond commercial “confidentiality” requirements. Didn’t matter — we made it work. The difference in quality and the real-world impact of that quality were far too important — for more than a decade we were the main supporting translation organization for the Cooperative Threat Reduction Program.

We had similar collaborative programs in the commercial sector in pharmaceuticals, medical devices, IT, rater training, and the list goes on and on.

Of course we built the company by taking market share away from the envelope switchers and the volume producers and the low-end providers who never had their talent collaborate on anything. They didn’t have time, or thought it was too complicated, or (more often) didn’t believe it “added value.”

They could not have been more wrong.

Most of those translation companies are no longer with us.

Collaboration is a choice.

Thank you, Kevin, for your excellent—as usual, though—article. I read it several times and, as I did, more and more questions arose. Devil is in details and some of these details look puzzling to me, to say the least.

First and foremost, you argue that the translation is largely intuitive, not rational. I unequivocally agree with this statement only to the extent it applies to literary translation. It was also true for technical and legal translation (TLT) three decades ago, during the era of typewriters and miles of bookshelves loaded with dictionaries and reference materials of every kind. However, these days, with humongous corpora of texts, usage statistics, search engines and contextual search strategies, online reference materials, etc., all readily available with a couple of clicks, TLT has become even more technology-based craft than art. Yes, it still requires understanding of the underlying concepts but any diligent translator can verify what the target text should look like in a matter of seconds by finding and reviewing similar contexts. Metaphorically speaking, TLT nature has transformed from paradigmatic to syntagmatic.

You write: “In a typical translation we make thousands of decisions, some visible and rational, but most invisible and highly intuitive.” Again, this is very true for a literary translation. In TLT, most of choices any diligent translator makes can be relatively easily made and verified by referring to respective terminological sources and/or bilingual documents of similar content.

The only area where TLT translator has to use intuition and educated guesswork these days is the source text. Too often, we struggle with internal corporate lingo, non-standard terminology, irregularities of all kinds, poor phrasing and obvious errors.

I would dare to say that widespread use of CAT and MT tools along with online verification techniques further transforms TLT process into something similar to Ford’s conveyer belt with the only difference: Ford workers used highly standardized parts and procedures to assemble a car while modern TLT translator has to deal with the source components (text) of various degrees of imperfection and, nonetheless, to produce a translation in compliance with the industry quality standards.

Furthermore, these days TLT becomes more and more integrated into much broader context such as web-based applications, software development, online publishing, etc., all of them being subject to numerous requirements and standards requiring TLT translator’s compliance in every aspect of production. The translation process becomes more and more structured and pre-defined leaving less and less space for personal preferences, including any bias.

Now, what kind of confirmation bias TLT translator can suffer from under these circumstances?

On a general note, what is called confirmation bias in psychology is just a pathological extension of a perfectly normal and productive ability of any human to use similar tools, skills, and patterns in similar situations without repeatedly going through a trial-and-error process. Yes, it is an intrinsic, built-in feature that allows to create mental “standard operating procedures”, shortcuts, macros and collections (“libraries”) thereof thus increasing productivity and efficiency of any repeated activity.

Second, a concept of collaboration you use is too vague to relate it to confirmation bias or to view it as an antidote thereto. Again, the devil is in details.

Collaboration (I would call it liaison) among the members of a translation team is a must, indeed. Collaboration with fellow translators at the ATA conferences by sharing your professional knowledge and skills should definitely be praised and respected. But collaboration with the project manager is totally different beast. Forgive me for my being what may appear cynical but in the latter case the word ‘collaboration’ is, as a rule, used to have a translator do something well beyond his/her professional duty as stipulated in the Work Order and do it for free. Like many other buzzwords of modern discourse, the word ‘collaboration’ is used too frequently (alas!) to literally extort translator’s time (idem money). Example: Review of and response to so-called ‘in-country review.’

Thanks for your very detailed and thoughtful reply, Igor.

There are several aspects to your comments, so I’ll try to tackle them individually.

I would argue that confirmation bias is so intrinsic to our experience of the world that we often cannot see it at all. Yet like an imperfect prism it diffracts white light uniquely because of the flaws and imperfections in the crystalline structure.

It’s axiomatic that all translators are writers at their core. We use words to project reality, and those “reality-projection filters” are manifestations of our personalities and experiences.

A good example of this is the kind of lexical biasing any algorithmic analysis of our writing will show. Run any large body of our translations or texts against lexical frequency tables and you can see our personalities emerge.

Donald Foster at Vassar has done a great deal of research on attributional theory in language, showing that it’s possible to identify the author of any anonymous text by simple lexical analysis. He was the researcher who unmasked Joe Klein as the author of “Primary Colors” by examining how his use of language revealed specific and unique properties.

It’s often said that technical translators are less “creative” and that any good generalist translator can become a competent technical or legal or financial translator simply by having access to the right terminology. You and I both know this is an absurd claim, but it’s a commonly held myth that I had to refute regularly when I was doing ATA PR (and it will also be the subject of a future blog post).

So let’s talk examples in Russian TLT.

It’s instructive and revealing that the best translators learn from each other constantly. None of us is perfect, and in fact sometimes we are even WRONG. Imagine that. No matter how clever a solution I may have found for a particular passage, there’s a good chance that Lynn Visson has done it better at some point in her career at the U.N. or that Natalia Strelkova has come up with a better solution during her 20+ teaching career in Moscow. You can test this (I do) by reading and reviewing their own translation solutions in their respective books “From Russian into English,” and “Introduction to Russian-English Translation.”

Two quick examples.

Take this simple passage:

В лаборатории много месяцев решали проблем несвоевременного свертывания крови

My version:

“The problem of delayed coagulation was the focus of lab work for many months.”

I liked Natalia’s better:

“The lab worked for many months on the problem of delayed coagulation.”

Now we both know that almost every translator working into English is going to make a major error in this sentence. Nearly every one is going to say the problem was solved (or that there were multiple problems, when the Russian is really suggesting different aspects of the same problem, which is why both our English translation use the singular “problem”). Even if you have enough skills to navigate the vagaries of aspect in Russian, you will still come up with a sentence that is structurally much different from what other translators produce. As you can see, for example, I prefer “focus” because I tend to think in terms of optics (see the first example in my response above) and also because in U.S. English usage, we “focus” on things a lot. There is, of course, no word “focus” anywhere in the Russian source text. But I would suggest that I’ve conveyed the idea successfully because the long amount of time in the lab suggests that it was a focus, a priority, and quite difficult.

Here’s another example where I like my version better than Natalia’s:

В интересах мира – отказ от всякого рода ядерного оружия

Natalia’s version:

“Progress towards peace demands that all forms of nuclear weapons be scrapped.”

My version:

“All nuclear weapons must be renounced if peace is to have a chance.”

The biggest problem I had with Natalia’s version was the word “scrapped,” which, as you know, has technical meaning, particularly in the context of the CTR program (also, “demands” seemed oddly too strong). But above all notice how we’ve come at this sentence from two fundamentally different directions and conveyed it in two quite distinct ways (one could argue mine is too Western and optimistic in a JFK sort of way).

As the saying goes, “Ask two translators, get three opinions.” 🙂

All these decisions and proposed solutions are the work of our “reality projection filters,” which, like all filters, are biased. It’s good to acknowledge these biases and imperfections as a way to appreciate how much we have to learn from each other.

Thanks again for your very detailed response.

Thank you for your prompt response. You’ve made quite a number of valuable clarifications and provided excellent examples supporting my comments.

You write: It’s axiomatic that all translators are writers at their core. We use words to project reality, and those “reality-projection filters” are manifestations of our personalities and experiences.

As to the first part of this statement, I’d rather be more cautious. There are quite a number of reasons why SMEs become TLT translators and, in addition to professional knowledge and experience in certain fields(s), it takes a lot of reading, excellent memory, and linguistic intuition (again, based on memorizing certain patterns and rules) to become a successful TLT translator. However, a translator uses words not to project reality, but to project another projection of reality (which is the source text).

Hence the conceptual difference between the writer (the originator of the text being translated) and the translator (projecting or transposing this text into a different symbolic and semantic system). Possessing writing skills is a must for any translator, indeed. However, as opposite to a writer who is limited only by his/her imagination, the translator is literally chained to the source text and his/her writing flexibility zone between Scylla of accuracy and Charybdis of completeness is very narrow. Metaphorically speaking, navigating through these waters does require knowledge of reality but navigation skills are much more important.

This is exactly why I doubt if your reference to algorithmic analysis of our writing is valid. It is not our writing. It is a reflection (inevitably distorted and rendered in totally different linguistic and cultural context) of the originator’s writing. In terms of optics, we, the translators, produce an imperfect reflection of light received from an imperfect prism (already distorted by the flaws and imperfections in the crystalline structure) onto an imperfect surface.

While I wholeheartedly agree with you with respect to an absurd claim you mentioned, devil is again in details. As opposite to literary translators, technical translators are “differently creative”. Their creativity primarily aims to restore the intent and meaning of the source in consonance with the reality and then render it in (or transpose into) a different linguistic system while to literary translators a “reality” component is totally different in its nature.

Now, let’s review the examples you provided in connection with my comments.

Passage #1:

В лаборатории много месяцев решали проблему несвоевременного свёртывания крови.

Your version:

“The problem of delayed coagulation was the focus of lab work for many months.”

Natalia’s version:

“The lab worked for many months on the problem of delayed coagulation.”

You explain the reason why you used the word “focus” by referring to your thinking in terms of optics (i.e., confirmation bias). That, probably, would sound plausible with respect to any translator but you. Knowing your extremely scrupulous approach to accuracy and ability to literally “live within” a text being translated, it’s hard for me to believe that your proficiency in optics inferred this addition. Long time this lab had to spend to address this problem does not suggest that it was a high-priority one (personally, knowing wide-spread research practice in that country, I would think that the opposite is true). Without a context, I can only guess that you simply tried to augment the emotional intent of this statement rather than fell victim of confirmation bias.

Passage #2:

Here’s another example where I like my version better than Natalia’s:

В интересах мира – отказ от всякого рода ядерного оружия

Natalia’s version:

“Progress towards peace demands that all forms of nuclear weapons be scrapped.”

My version:

“All nuclear weapons must be renounced if peace is to have a chance.”

My special thanks for this example. It perfectly illustrates my statement: “The only area where TLT translator has to use intuition and educated guesswork these days is the source text. Too often, we struggle with internal corporate lingo, non-standard terminology, irregularities of all kinds, poor phrasing and obvious errors.”

Even without a context, it is obvious that the source sentence is a typical example of newspaper-like narrative – ambiguous, loosely formulated, and terminologically incorrect.

Let me start with the second part of the sentence. First, the expression “отказ от ядерного оружия” is meaningless because it is incomplete. “Отказ от использования ядерного оружия как средства разрешения международных конфликтов” is one thing, “отказ от разработки и хранения ядерного оружия” is totally different thing, “отказ от ядерного оружия путём его ликвидации (уничтожения)” is yet another different thing. Maybe, the context suggests otherwise, but, in general, translation of this language is pure guesswork.

Another improper rendering is “всякого рода”. It is totally redundant because “ядерное оружие” is the most general category that includes all types of nuclear weapons—the very same way as “non-nuclear (or conventional) weapons” is another most general category.

Now, the first part of the sentence (“В интересах мира”) is also ambiguous (unless the context suggests otherwise). Again, it’s translator’s guesswork whether the author meant “peace” or “world”. (It’s worth noting that this distinction existed before the 1918 reform of Russian orthography (‘мир’ and ‘мiр’)).

As we see from the above, a simple idea of ‘renouncing nuclear weapons as one of the ways to achieve worldwide peace’ is rendered in such awkward manner that the translator would have to spend much more time trying to identify its meaning than to formulate it in the target language.

Thank you again for this opportunity to discuss professional matters in your blog.

Thanks, Igor, for that very insightful and thorough reply.

It seems that we are more closely in agreement after all.

For example, I agree wholeheartedly that source text ambiguity is often the greatest barrier to understanding and poses the greatest challenges to interpretation and understanding.

My point would be that our respective biases nonetheless lead us to different assumptions and, therefore, conclusions.

Your assumption, in the first Russian text example, is that the lab is located in Russia and therefore the long time frame suggests something other than “focus,” while my own bias led me to a different contextual assumption; specifically, that the Russian text was reporting results from a lab-to-lab program (and the lab referenced was in the U.S. and the results are just being reported in Russian) where those timeline priorities are quite different. And that’s because so much of the translation work we are actually asked to perform — the kind that is properly funded, of course — is often tied to serious collaborative lab work where results actually matter. In U.S. practice, extended effort = focus, as you know.

The best way to resolve these is through context, of course. If we were able to progressively expand our view of that sentence to include ever more text around it, then the picture would become much clearer and the choices more obvious.

But without the context, it’s our own biases that we bring to the table that determine the choices we make.

And this brings us to a crucial point. Since every translation is just a small piece of a much larger ongoing conversation — hundreds of researchers, years of effort, highly complex and interrelated programs, extremely complex equipment and systems — the context available to us at any one time will always be relative and limited. All the online research we perform, all the events we attend, all the programs we participate on, are designed to try to capture as much meaning and context as possible. But we can never get it all. We are always going to have to deal with our own assumptions as we face the text.

Where you and I still seem to differ is whether confirmation bias is stronger with authors rather than translators, and in the case of translators, whether it’s stronger for literary translators than for those working in technical subjects.

I propose a thought experiment to illustrate how confirmation bias is active in all three cases.

We already agree that the author of an original work is prone to confirmation bias.

So for our thought experiment let’s have the original author instead be a painter, who paints in complex water colors a winter landscape complete with fabulous churches festooned with brilliant colored cupolas and blowing snow and trudging churchgoers struggling to shield themselves from the cold. We agree this original work projects all the biases of the original author/painter.

The literary translator/painter sits down in front of this landscape water color painting and sets up his own canvas. He must now render on that canvas a version of the winter landscape scene of his own. Except the translator is working in a different language and culture, so let’s have the literary translator use colored pencils in a different range of color palettes as a way to try to capture that scene, and in a pencil sketch rather than in water colors.

If I understand your point correctly, there’s a broader range of variability in the winter landscape painting that makes the literary translator more prone to confirmation bias in painting a “translation” of it using pencil sketches. In other words, there’s more likely to be the personality and choices of the translator present in that pencil drawing.

So for the technical translator, let’s have the oil color painting be an extended cut-away view of a complex 19th century pocket watch in brilliant colors. And let’s have a room full of 40 technical translators arrayed in successive lecture-hall-style arc rows around that oil color painting in the center of the room, each with a white empty canvas to draw on and a set of color pencils in a different range of color palettes, e.g. colors that do not match the oil colors in which the painting was done. So proper shading and matching of colors to most closely approximate the original water color painting is required.

Certainly the pencil sketch artists with the strongest artistic skills (equivalent to target-language writing skills) will have a huge advantage and likely paint some of the most compelling and accurate sketches. But I would suggest that it’s the pencil sketch artists with equivalent artistic skills but who’ve also collected, dismantled and assembled 19th century pocket watches for years, and have an intimate understanding of how all the pieces fit together in 3-dimensional scale, who are going to produce the most authoritative versions of that cut-way pocket watch.

But even if we were to compare THEIR versions, the EXPERTS’ versions, some would be superior in gearing, some in the balance wheel, some in the frontspiece, some in the color shading and some in perspective. Each is forced to work through those biases that are shading each of their respective views of the oil color painting of the 3-dimensional pocket watch.

If we collect all 40 pencil sketch versions and line them up against a wall, we will see some remarkable variation in work. The novices who can’t really draw will produce sketches that look more like smashed watermelons than like watches. Those who have some skill will produce sketches that look vaguely like watches, but will distort the 3-D view, or get the coloring wrong. Those who can draw but are not mechanically inclined (lack the subject-matter expertise) will lack the detail and scale perspective of the original. The gearing will blend with the wheels, or they will all blur together.

What I’m suggesting in all this is not just that confirmation bias is guiding all the myriad of individual choices that make the paintings so dramatically different (although it most certainly is). They are painting what they “see.” They make a blizzard of choices, and erasures, and color blending and shading based on what they “see.” But what each artist “sees” is quite different. That’s confirmation bias.

The greater point in all this is that there’s enormous benefit to taking all those paintings and lining them up against the wall and collectively examining what works and what doesn’t, who has succeeded most dramatically and who has failed, and learn about why that is so.

If we put the top 5 pencil sketches in one room and allow those artists to collaborate on a “best version” I think it would be the most breathtaking of them all, and at the end of the day is a dramatically and incomparably better way to produce stunning versions of pocket watches compared to the alternative of the 40 sketch artists all working alone, in different locations, producing work ranging from awful to marginal to excellent, and all in total isolation.

That’s the reality of the translation market today.

Kevin, the pencil-sketch model you provided is an excellent analogy that reveals the conceptual difference between our views.

The value of any model depends on the assumptions it is based upon. For the purpose of this discussion, I presume that none of the participants suffers from visual impairment or any vision disorders such as astigmatism, myopic/hyperopic disorders, etc. In other words, all of them have normal visual acuity (20/20 vision).

Also, I would emphasize the fact that the source is the painting of a complex pocket watch rather than an enlarged detailed photograph of the same watch. It is obvious that different painters would depict the same object differently depending on their perception, schools they belong to, and number of other factors. Just imagine what such watch would look like in Van Gogh and Paul Signac paintings But even most realistic paintings would contain certain distortions as compared to a photograph and, therefore, painting is a good analogy of the real (imperfect) source text for translation. By the same token, within the context of your model a photograph may be interpreted as a refined, peer-reviewed, and polished text such as an article from the Encyclopaedia Britannica or ASTM Handbook.

One component your model lacks is a reference point. I propose to use a detailed photograph of the same watch as such.

If all participants have 20/20 vision, they will see the same when a photograph is presented and there’s only one reason why the sketches they produce are so different: variation in their drawing skills, i.e. their ability to accurately reproduce what they see. (This, in turn, is determined by fine motor skills, spatial sense/reasoning/imagination, i.e., purely individual parameters, plus drawing experience, i.e., acquired techniques, skills, and the like.)

When an actual painting is presented, an additional factor comes into play, namely, the distortions (as compared to a photograph) of various nature (shape, position, perspective, shades, etc.) that impair each participant’s ability to correctly perceive and reproduce the image. Furthermore, what they are trying to reproduce is not a watch—it’s an artistic IMAGE of a watch distorted by painter’s perception and implementation. This is exactly what I called in my previous post “reflection of reflection.”

If we apply this model to translation, the assumption (normal visual acuity) would be interpreted as good linguistic expertise (what we call ‘a sense of language’), including, among other things, ability to read and understand the source text. The watch would be the ‘reality,’ the painting would be a real-life (i.e., imperfect) source text and a photograph would be an etalon text such as an article taken from ASTM Handbook and available online in both source and target languages (like a krypton standard).

Now, let’s conduct a mental experiment with participation of 40 professional translators tasked to translate an etalon text using any and all available online resources.

Naturally, 40 translated texts would be different in terms of terminological accuracy, style, etc. There would be a handful of translators with deep understanding of and experience in elaborate search strategies who would quickly locate both versions of the etalon text in both languages on the Web. The majority would diligently explore relevant target language resources to get a clear idea of the subject matter involved and to mimic their terminology and style. A handful of the least experienced would use their prior knowledge of the subject matter (the ‘reality’) to compensate for lack of online research skills.

The same, albeit more diverse (from smashed watermelons to industry-quality drawings), results would be obtained when the same 40 translators are tasked to translate a real-life text. The most experienced and diligent would search for target language texts that are as close to the source text as possible in terms of their subject matter, type, style, and terminology. Others would concentrate on terminology only searching through online dictionaries and, again, a handful of the least experienced would use their prior knowledge of the subject matter (the ‘reality’) to compensate for lack of online research skills.

In both cases, the outcome has very little to do with any type of cognitive bias. Poor quality of the least experienced translators’ translations is primarily due to their unawareness of and/or inability to use online resources (“drawing skills”). This is exactly why they would use incorrect terminology taken from other subject fields believing that it is applicable in this case.

Thank you for your time devoted to this discussion despite your extremely busy schedule.