The Future has an Ancient Heart: Why Predictions about the Future of Language Technology Always Go Hopelessly Awry

January 11, 2013

“Scholars and scientists who work on mechanical translation believe that within a few years the system may greatly increase communication, particularly in technical subjects, by making translation quick, accurate and easy.”

The New York Times – January 8, 1954

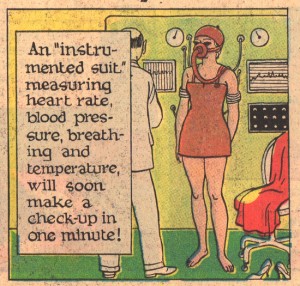

Technology gurus of the future, writing in the 1950s, predicted that today’s world would be exploding in brilliant and flashy flying cars with huge fins, space suits, jet packs, shiny edible clothing, huge rocket ships, smart-aleck talking robots, house-sized computers and comfortable Moon colonies.

Instead, the cars shrank, the space suits disappeared, the house-sized computers now fit in your hand, the robots are faceless wired Legos and the Moon colonies were erased from the drawing board before they even began.

The real technology revolution turned out to be exactly the opposite of the predictions.

Things didn’t get larger, they got smaller. The technology was not flashy, it disappeared silently into unimaginably more powerful hand-held devices.

Electronics did not fill rooms, it slid into pockets.

And what about all those newspapers they were reading during breakfast on the ultra-modern Moon colonies?

Nope, no moon colonies.

Also, no newspapers.

And machine translation is still clunky and unreliable nearly 60 years after the New York Times prediction above.

An outcome that’s exactly the opposite of the prediction.

How could all these predictions have gone so impossibly awry?

Predictions of explosive technological change are almost always wrong. What futurists think of as their own “imagination” is really a mirror reflection of what’s already staring them in the face that very day (such as the US space program in the 1950s) suddenly applied to the entire world (We’ll all live in space!), which is an unfortunately stale and unimaginative practice of taking whatever exists and simply extending it randomly into the future by making it larger or faster or more colorful or otherwise “futuristic.”

“Translating machines will soon take their place beside gramophone records and colour reproduction in the first rank of modern techniques for the spread of culture and science.”

Emile Delavenay

December, 1958

Futurists are overly seduced by the newest technology, most of which fails or is discarded or becomes outdated in the near term (8-track tapes, black-and-white TV, AM radio, the DeLorean) making what seems “futuristic” at the time unlikely to survive into the real future.

Hopeful technocratic predictions are also overly reliant on the views and opinions of engineers, who tend to have a narrow solutions focus that is surely admirable in its efficiency and focus (it got us to the Moon), but a bit too spartan and utilitarian for people to embrace (“I’m not wearing aluminum!”)

And that brings us to the most important reason that technology predictions fail:

Successful technology is always shaped by human interaction: Technology that does not improve or advance or align with human experience will be modified, rejected or ignored.

The philosopher, quantitative analyst and former Wall Street trader Nassim Nicholas Taleb describes in his recently published book Antifragile how the technology that’s succeeded over long stretches of human history is likely to survive into the future – and triumph against challenges – strictly by virtue of its hard-earned symbiotic relationship with humans.

So consider what did not change today in the face of our 1950s wide-eyed futurists’ whiz-bang space predictions of new things to come in our daily lives like “shiny synthetic space suits and nutritionally optimized pills”:

“Tonight I will be meeting friends in a restaurant (tavernas have existed for at least twenty-five centuries). I will be walking there wearing shoes hardly different from those worn fifty-three hundred years ago by the mummified man discovered in a glacier in the Austrian Alps. At the restaurant, I will be using silverware, a Mesopotamian technology, which qualifies as a “killer application” given what it allows me to do to the leg of lamb, such as tear it apart while sparing my fingers from burns. I will be drinking wine, a liquid that has been in use for at least six millennia. The wine will be poured into glasses, an innovation claimed by my Lebanese compatriots to come from their Phoenician ancestors, and if you disagree about the source, we can say that glass objects have been sold by them as trinkets for at least twenty-nine hundred years. After the main course, I will have a somewhat younger technology, artisanal cheese, paying higher prices for those that have not changed in their preparation for several centuries.”

The point here is not that old technologies are always best – after all, I use voice-recognition technology in my own translations of physics on a hardware system I designed myself – it’s that technologies that old have survived an astronomically large number of destructive challenges over the centuries and yet have survived intact today – in fact, prospered from those challenges – because they are imperceptibly woven into the human experience.

Language Technology

Language is a special case in technology because it’s the most essentially human of all possible cognitive activities. That makes it very nearly organic in evolution and behavior, erratic and unpredictable, frustrating and counter-intuitive, and unusually resistant to successful algorithmic manipulation.

Recent research in cognitive psychology has consistently demonstrated that human intelligence in decision-making is at its core overwhelmingly emotional, often irrational, and exceedingly human-bias-driven. So that makes it a highly intuitive activity, a domain that has continued to frustrate researchers in artificial intelligence (AI) since its inception.

The obsession in AI with all things “logical” as the core concept in defining “intelligence” is a false artifact of a failed imagination – and a trap Hollywood has deftly avoided.

“I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.” – HAL, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

In MT, these constraints, among others, force persistent errors as the code scrambles to keep up with the sprinting language. This rampant error propagation in MT is also why post-editors are so crucial to every step of the machine translation enterprise.

Today’s post-editors function much like the mechanic who takes up permanent residence in the passenger seat of the forever failing two-seater Jaguar sports cars of the 1960s that would break down endlessly, assuming that they started at all.

Upgrade the code – problem solved

Improvements in technology have surely improved the quality of MT, which is why it has important and valuable applications in gisting, high-volume/low-quality translation and online on-the-fly translations — all areas where it will continue to expand and likely dominate.

The temptation to definitively solve the MT problem once and for all — to replace professional human translators –by “perfecting the technology,” however, much like re-engineering the Jaguar, fails on the nature of language itself.

Our own scientific study of language in linguistics reveals that ambiguity in language is a feature, not a flaw. It’s a recurring, inbuilt functionality that continually re-asserts itself and makes language a wonderful tool for describing a fuzzy world of ambiguity and inference and subtlety and nonlinear complexity and, of course, the downright messy realities of human relationships.

Including human relationships with technology.

The cost of failed predictions

You would think that this disastrous record of preposterously bad predictions would at least shame commentators into adopting a more modest or humble stance on language and technology, but hardly a week goes by today without yet another “Star Trek Universal Translator” article that comes to all the wrong conclusions.

This week The Economist set out to explain how the Universal Translator in Star Trek reads brain wave activity to accurately translate inter-galactic languages in the 23rd century. This is quite well-known in the science-fiction lore, and it was an unusually creative solution at the time because the Star Trek script writers were, uh, writers, who knew all the confounding rules responsible for the subtlety and power of language, which would certainly defeat any computer analysis they could reasonably foresee, even in the 23rd century.

But The Economist then promptly swung around and without even blushing – or hoping nobody noticed the card deck change – gave glowing reviews to a silicon-based, non-intuitive, non-contextual, non-brainwave-reading, early-21st century technology that is slavishly tied to individual words – a creaky, mistake-spewing Stone Age technology by comparison.

The future of coders

Perhaps what’s most striking in language technology predictions is the complete absence of even a hint of a prediction of the demise of computer programmers. After all, technological advancements in the modern motor vehicle have all but eliminated backyard screwdriver mechanics and tinkerers. Typewriter repairmen have been gone for decades. And nobody repairs computers today, anyway – it’s just faster and cheaper to buy new ones. And how many new apps do you need when 1 million have already been written?

As technology improves, it becomes more transparent, reliable, and cheaper and dramatically less insistent on intervention.

Translators are the past – and the future

Translators should be the least concerned with advances in language technology. They have the one skill set that is essential to understanding and conveying meaning in human language.

That means that they are by far the most crucial link in the chain of viable MT.

The computer programmers, on the other hand, might want to think more carefully about their future, especially given the inverted way these technology predictions turn out. They may be tomorrow’s backyard screwdriver mechanics and tinkerers who suddenly find themselves out of work.

And can we put an end to the vaguely dismissive talking-down to translators from those failed technologists? I’m weary of watching the alchemists lecture us chemists – you know, the people who actually do all the valuable work, have done so for millennia, and will continue to do so in the future.

Hubert L. Dreyfus was way ahead of his time when he wrote “What Computers Can’t Do” (1972), updated in 1979 and again in 1992, under the title What Computers Still Can’t Do, and Mind Over Machine, 1986. Your article pretty much reconfirms the validity of his positions.

Translation is Not About Words. It’s About What the Words are About.” Indeed.

Thanks for an enlightened reminder…

I’m familiar with Dreyfus’ books and certainly in the interim the persistent and overwhelming hype about computers’ taking over every aspect of human labor and creativity — and doing a drastically better job than humans ever could in every way — has far surpassed the hysterical phase of Dreyfus’s time and is now today slowly crossing the boundary into the apoplectic fit phase.

The challenge lies in sorting out what computers do best from what humans do best. In those areas where their capabilities overlap, it’s a challenge to find the optimal distribution, especially when having to deal with the inevitable bias of the media and popular culture to dramatically overstate and exaggerate every aspect of technology and its capabilities.

Kevin,

Thank you for this. I enjoyed it very much!

A reminder to all of us that we better stick to the advice of experts, while may be more boring than the flashy predictions of the average futurist, they certainly help set expectations in a bit more realistic fashion. Re the Economist, news papers are required to sell ads and unfortunately without the eye catching headlines and unrelated teaser paragraphs, they probably would not do as well on ad sales…

For complete disclosure, work for a Machine Translation technology company but I am a new comer to the industry. Analyzing the language industry and especially its language technologies as a business man, I think Machine Translation should be accepted for its real commercial value – as a productivity tool for translators and as a means to enable real-time multi-lingual communications using online channels. Many of these channels are quite forgiving for language imperfections (true also when no translation is involved) and so provide business value to those who choose to use them. Given that, experts in the field would not tell you that Star Trek translators are just around the corner, they would also agree with your final sentiment about the future of translators. As Machine Translation evolves, it will provide increasing value to translators and business uses alike. And as for the Star Trek universal translator… well, I am still waiting on the next movie in the series to see how this technology evolves 🙂

Udi wrote “I think Machine Translation should be accepted for its real commercial value – as a productivity tool for translators”

For an experienced translator, Machine Translation is only useful as a productivity tool when the proposed translations it produces are better than nothing.

Faced with a proposed translation of a sentence, a translator must assess the accuracy and quality of the proposed translation and decided to: 1) accept it as is, 2) modify it, 3) discard it and start over.

In case 1, the proposed translation has very likely helped the translator’s productivity and in case 3 the proposed translation has hurt the translator’s productivity because the translator expended effort and annoyance before starting fresh. A proposed translation that has to be discarded is worse than nothing. A proposed translation that has to be modified may also be worse than nothing.

How good does a proposed translation need to be to help a translator’s productivity?

Let me suggest an answer to that question by looking at my experience editing work by other translators.

As a professional translator editing the work of other professionals whom I know, I find that in the aggregate their work falls in case 2. On the whole, their work is good (That expectation, based on experience with their work, is why I accept to edit their work.), but they are human and there is a need for another set of eyes.

The reason why I only edit translations done by other professionals whom I know is because I have been burned too many times: there are many translators out there—let me be polite and call them apprentices—who should only be working under close supervision because the work they turn out falls firmly in case 3 (in the aggregate). Sending their work out to unsuspecting translators for editing is not an alternative to the close supervision these people need. Doing the translation over would be more productive, less annoying and achieve better results than editing their work.

I conclude that for machine translation to help my productivity, it needs to propose translations that are better than translations by apprentices and nearly as good as translations by professionals whose work I’m willing to edit.

Machine translation is not much help to my productivity unless it’s nearly good enough to replace me.

Bruce, what amazes me is that if clients really wanted to significantly increase turnaround while maintaining quality, it would make better sense to invest in a completely different technology — one that does not introduce errors right out of the gate that are themselves heaped upon stilted and awkward phrasing.

Why not use human translation via voice-recognition technology? With proper training of the software, it produces a much lower error rate and the final product will reflect the writing skills, subject knowledge and elegance of the translator.

Alas, there’s no money to be made in this case by “MT experts” as it bypasses them entirely. But it does produce a superior product for the client at much lower cost and at dramatically higher turnarounds.

Good to see your pen is as sharp as ever.

You know the translation business extremely well. It is one of very, very old professions, which is still thriving against all odds (smile). Every day there are popping out new companies, which are trying to make a living in translation business, but the supply of good translators is limited and their output is also limited.

The development of instant communication is pushing translation prices down and the majority of translators are accepting this as a fact and they do nothing about it, because they believe there is nothing they can do.

Good translators are in a bit better position, as at least some of them have good customers and therefore are able to survive the downward proz biding spiral for now. But for how long?

I think the time has come that we use the instant communication to translators’ advantage and start to think out of the box and figure out a new approach to translation business, where we will not be at such mercy of the resellers of our work.

I believe good translation is like gold. There is a limited supply of that.

So let’s figure out the way for the price of our work to be valued like gold.

We deserve it and it’s about time.

Any ideas?

Hi Radek, nice to hear from you.

Do keep in mind that the re-sellers come in many flavors. Some add value in important ways by providing talented graphics support, engineering expertise, printing, voice-over and video, subtitling, etc. (like my former company ASET) while others are little more than error-prone data servers that pass along the work of others.

Many excellent translators have found a nice balance in working in cooperatives with their colleagues where they’re able to leverage their expertise and rely on each other for review and revision services. That’s a nice model as far as it goes for the smaller segment of the market.

Once you cross over to major corporate projects in 25 languages and across dozens of media, though, you ultimately need to have these ventures capitalized, and it costs more money than you can imagine to do this. I know, I’ve done this myself, and the funding requirements are simply staggering. I’ll be writing more on this subject in the future.

Thanks again for your comments.

Marvellous to read. First of all, because of wording. For a non-english speaker (russian) this a feast for mind and ears (had to skim multitran for some translations)). What is your opinion, by the way, on crowd-sourcing? i this regard, I would appreciate your help at naming some sources (forums, blogs) that a En-Ru translator in radar field could use just for “likbez’a”))?

Thanks, Kevin, for writing this. It’s brilliant.

A pleasure to read ! A really intelligent demonstration in a brilliant style.

Loved the article from A to Z. Thank you!

Excellent assessment of the present situation, Kevin.

>>> I believe good translation is like gold. There is a limited supply of that.

So let’s figure out the way for the price of our work to be valued like gold.

We deserve it and it’s about time. <<<

I like Radek's statement. But how do we proceed?

Thanks, Doris, for your reply.

I think we’d have a hard time arguing that translation, even good translation, is as rare as gold, and the value of gold in large measure comes from that rarity. For example, there are successful crowdsourcing translation projects that leverage the talents of an enormous number of nonprofessionals and some of them do a fine job (the TED conferences are done this way) and this will likely increase in the future.

The consistent effort to accelerate volume and turnaround through the use of MT technology suggests that the largest untapped market is the low-quality, high volume market — the WalMart segment of the market — which I’m sure you’d agree is an area providers like you and I would want to avoid.

As I told Radek, the solution for individual translators who wish to bypass “agencies” is to pool their skills with colleagues they know and trust and offer letter-perfect final publishable translations. Collaboration is essential to achieve this, and the best translators know and practice this already. There will always be a requirement for good translation companies that are properly capitalized and have the expertise and resources to handle translation and localization on dozens of platforms and in over 100 languages on short turnarounds. It makes no sense to try to displace or replace these companies unless you have the ability to capitalize them yourself over the long run.

The market is surely large and diverse enough to accommodate all these players.